IntroductionPeople are always surprised that Black people reside in the hills of Appalachia. Those not surprised that we were there, are surprised that we stayed. My family has lived in the region since the 1800s, and to disregard the Black mountain presence is to erase both the past and the present.

Chroniclers of Appalachian history have sometimes ignored the existence of Black people in the Appalachian South because of the belief that the ScotsIrish descendants who settled in the region were mostly poor and therefore couldn’t afford slaves. But records show that early Appalachians did in fact own slaves, and beyond that, the African presence in Appalachia was documented as early as the 1500s, when enslaved Africans and free persons of color arrived in the region with Spanish and French explorers. Though mountain slavery wasn’t like the large enforced labor camps of the Deep South, enslaved people worked on farms, in mines, logging, and in kitchens before and after manumission, and the work was still often punitive.

After the Civil War, many freed Black people became landowners and lived rural lifestyles similar to those of their white counterparts. Black Appalachians remain in the region to this day, with nearly two million Black residents contributing to the region’s rich legacy of music, art, literature, and foodways.

The invisibility of the Black presence in today’s Appalachia is mostly due to the prolific misrepresentations of Appalachia as a whole. The term

Appalachian (in regard to people) was popularized in the 1960s, when President Lyndon B. Johnson formed the Appalachian Regional Council with the intentions of strengthening the economy of the area, but by design no one considered that Black people were among the residents of the region. When Frank X Walker founded the Affrilachian Poets, a writing group that I’ve been a part of for thirty years, he discovered an entry in a dictionary that emphatically stated Appalachians were “white people indigenous to the Appalachian region.” In 2005, Appalachian scholar and librarian Fred Hay petitioned the Library of Congress to change its subject heading to “Appalachian (People).” Prior to that, anyone searching for archival information about the people of my region within the Library of Congress system had to type in the term “Mountain Whites.” And even today Dictionarydotcom says an Appalachian is “a native or inhabitant of Appalachia, especially one of predominantly Scotch-Irish, English, or German ancestry.” No mention of Indigenous or Black people.

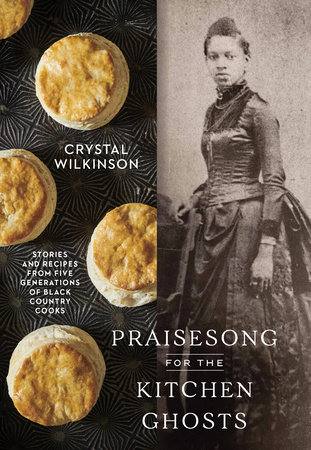

While the rampant stereotype of the white hillbilly remains, Black people have always been of these hills, and I really need to look no further than my own family as proof. My family has lived for five generations in the hills of Casey County, Kentucky, in a little hamlet called Indian Creek. Our homeplace was cradled by tree-covered hills in the south central part of the state, at the head of Green River. Casey County was formed in 1806, two years before Aggy of Color, my fourth great-grandmother, was likely brought from Virginia to the new territory as an enslaved child. This book is about my foremothers, my kitchen ghosts, about the ways in which the foodways of the hills were passed primarily down through the women in my family, to me, and how I will pass them on to my generations.

The concept of the kitchen ghosts came to me years ago when I realized that my ancestors are always with me and that the women are most present while I’m chopping or stirring or standing at the stove. The art of cooking and engaging with my kitchen ghosts made me realize that food is never just about the present—every dish, every slice, every crumb and kernel also tethers us to the past.

In these pages you will meet my culinary matriarchs and see their influence in the foods I cook and the way I cook them. These women, some of them dead for two hundred years, still affect the ways in which I hold my hands, the tools I choose, the way kitchen work feels in my body.

Aggy of Color (who later became Aggy Wilkinson) was born in 1795 and presumably brought to Kentucky when the white Wilkinsons moved from Powhatan, Virginia, to help settle Casey County, Kentucky, in 1808. Though I don’t know what her duties were as a Black woman in the 1800s, she was likely enslaved at the beginning of her life. There are varying accounts, including census records that indicate she became a freed woman of color when she married Tarlton Wilkinson, a white man. From Tarlton and Aggy came our lineage, and the spark of my curiosity about her life and foodways. Aggy is the inspiration for this book, though I had to rely on spirit and imagination to conjure her. Because of the deficit of historical records for Black people, especially Black women, she lives on these pages as an amalgam of history, imagination, and divination. She is the flesh-and-bone lens through which I view the tyranny of slavery and both its historical and personal impacts on past and present culinary traditions in my family.

One document that I became obsessed with is a deed in which Tarlton gives Aggy a long list of household items. I’ve often wondered why he would have made this transaction legal, because he certainly wouldn’t have been bound by law since he owned her. The items he gives her include a table, six knives and forks, six plates, and earthen vessels in which to cook. If they were husband and wife—even if secretly at the time—why did he feel the need to deed her these simple household items that she would have used every day? I often imagine her telling him that he owned her and their ten children, but there was nothing that was hers. Later, he deeded her land, but it’s fascinating to me as a cooking woman to think that her first burst of empowerment in 1824 may have come in the form of the accoutrements for her kitchen.

Slavery on farms in Kentucky was different than the larger plantation complexes in the Deep South, in that enslaved people worked intimately with their owners. So that’s how I see Aggy and Tarlton—laboring side by side in their house and fields. Though she became his wife, there is no doubt that she was also his property. I have little notion of romance between them. I imagine her as a girl working in the kitchen of Tarlton’s father before he took her and a small band of five or six enslaved workers to his own farm to work. Aggy grew a small garden near the home and cooked for Tarlton, their children, and other enslaved workhands.

While there would have been some domesticated animals on this farm, I’m sure Tarlton and the other men would have still hunted deer, elk, wild turkey, and even squirrel and possums, depending on income and nature. Grandma Aggy would have been a magician with those meats and paired them with Irish potatoes, green beans, corn, and onions from her garden and made a hunter’s stew or even some version of Kentucky’s famous burgoo, a regional stew made from the kill of the day and available vegetables and thickened with oats or cornmeal.

Aggy and Tarlton had three sons and seven daughters who helped them cook, tend the land, and take care of the animals. Those ten children married and began families of their own. The sons—Bowlin, Frederick, and Alfred— married Burdettes and Beards and Tennessee Wilkinsons. The first Wilkinson daughters married Napiers and Riffes, Mortons, and Duncans. Though little is known about the intimate lives of these first children, my family’s direct lineage begins with Bowlin and grows deep and wide on both my grandfather’s side and my grandmother’s. Bowlin’s sister Patsy bought, married, and freed her husband, William Riffe.

Among Aggy and Tarlton’s children and grandchildren were blacksmiths and business owners, but farming was in their blood. These men’s and women’s lives were still marked by slavery; however, they continued growing and preserving traditions they learned from their father, a white enslaver’s son who came to America from England, and their mother, a Black formerly enslaved woman with the ways of Africa still coursing through her veins. These first Wilkinson children and their grandchildren brought much of that rich amalgam of culinary history with them as they moved forward with their own generations.

Copyright © 2024 by Crystal Wilkinson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.