IntroductionBefore the big-money developers descended upon downtown Brooklyn in the early 2000s to scrub away the patina of urban grit for the sanitized monotony of mass chain retail, Fulton Street was an eclectic commercial destination, bustling with the kinds of shops where you could buy a new pair of Jordans (shrink wrapped in plastic, of course), a mixtape, and a gold chain, all at the same establishment.

With pens, notebooks, and a voice recorder in hand, we spent a drizzly November Saturday in 2015 walking up and down what is known by many as Fulton Mall, which, even in the wake of gentrification, is still home to one of New York’s busiest shopping districts and, historically, one of the world’s foremost meccas for Hip Hop fashion. This research outing was in preparation for a podcast we were starting, the first episode of which would be about an accessory particularly meaningful to both of us—nameplates. While we wandered, we kept our eyes peeled for the surviving jewelry stores of an erstwhile era—the type with Jesus pieces, diamond-encrusted Mickey Mouse pendants, and three-finger rings glimmering in window displays.

Though the number of shops that specialize in this jewelry has dwindled in the past two decades, nameplates remain coveted accessories for many. Little did we know that our excursion that day would mark the beginning of a journey that would continue to evolve over the next five years and open up countless new relationships, unearth understudied historical connections, and result in this book.

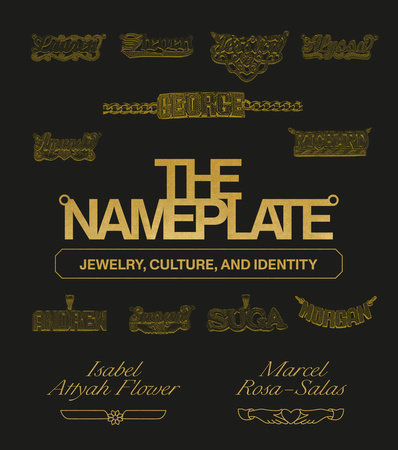

What is a nameplate? Nameplates are a style of jewelry in which names, or other significant words, are sculpted from precious and base metals and worn as necklaces, earrings, rings, belt buckles, and bracelets. Like most expressions of culture, nameplates have no singular origin.

Adornment in the form of language is as old as writing itself, and there has been, throughout history, an inherent and undeniable power in decorating one’s body with one’s own name. As the nameplate traversed an array of locales across the globe, it flourished into myriad syncretic design traditions that illuminate the many ways people use fashion to make statements about their individual identities and cultivate a sense of community. Nameplate jewelry’s origins can be traced as far back as ancient Egypt. Pharaohs and members of the upper classes dipped gold signet rings engraved with hieroglyphic writing into wax as a way of signing official documents. From the Victorian-era mourning jewelry worn in English and Judaic traditions to family heirlooms crafted in Hawaii and Panama to coming-of-age objects for numerous different cultural groups, the nameplate’s historical lineage spans a vast range of contexts. The 1987 excavation of the RMS

Titanic revealed an early-twentieth-century nameplate bracelet; the name Amy, forged in diamond-encrusted silver script, was set in a rose gold curb link chain.

Nameplates have been pivotal sartorial items for pop cultural figures both real and fictional, including Hip Hop pioneers Grandmaster Flash, Big Daddy Kane, LL Cool J, and MC Lyte. Renowned

bachatero Antony Santos sported nameplate necklaces on two of his album covers; one featured his first name, the other his full first and last on two lines, and both were rendered in bold block capitals. Bayamón, Puerto Rico–born boxing champion Héctor Camacho wore his signature MACHO pendant with pride—the oversized, singleplated Chinese lettering (also known as “Kung Fu”) nodded to the influence of the era’s B-boys and B-girls.

Nameplates have also been requisite to the wardrobes of famed television and movie characters like Spike Lee’s Mars Blackmon in the 1986 film

She’s Gotta Have It and Radio Raheem in 1989’s

Do the Right Thing. The latter’s matching four-finger “LOVE” and “HATE” rings were crucial props in one of the film’s most memorable scenes. Likewise, Dolly Parton’s Doralee Rhodes in the 1980 blockbuster

9 to 5, Sarah Jessica Parker’s Carrie Bradshaw in

Sex and the City, and Drea de Matteo’s Adriana La Cerva in

The Sopranos all rocked nameplates of note.

Yet while the nameplate has multiple, overlapping progenitors, we—and many of the people we spoke to while making this book—became familiar with this jewelry through the specific styles, contexts, and cultural traditions that make up the manifold phenomenon that is American Hip Hop. Individual style and the ability to showcase oneself in a unique way were requisites of Hip Hop’s four founding pillars: DJing, MCing, breaking, and writing graffiti. Each medium cultivated expertise by way of personalization, whether a particular way of mixing and transitioning beats, a singular rapping flow, a never-before-seen dance move, or an eccentric hand style. The intent of these creative endeavors was to develop a persona that was distinct and highly recognizable, and artists often created a moniker to accompany their craft. These names, alter egos of sorts, are an essential part of Hip Hop’s particular brand of autonomous self-expression. Many of these monikers were displayed to the world through jewelry items, and their sartorial influence spread through nightlife and other key occasions of social gathering and intersection. It is, in many ways, through the influence of Hip Hop that the nameplate has become a contemporary, mainstream, and global sensation.

We are what we wear. But style—as a site of self-declaration—is also a vector of power. Embedded in practices of self-presentation are also heftier matters, such as the political and cultural contours of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, and gender, which inevitably inform not only who wears what, but how fashion choices are perceived and even policed in the public sphere. Hip Hop’s emergence and rise to popularity also coincided with periods of extreme and targeted political disinvestment, poverty, and oppression, especially in New York City, from arson rampant in the Bronx in the 1970s to Reagan-era austerity measures in the early 1980s and the violence that accompanied the concurrent arrival of crack cocaine. As cultural historian Jeff Chang has noted, the Hip Hop generation has often been characterized as “invisible,” which, in retrospect, seems unthinkable given the profound impact of their creative production on the rest of the world in the decades that followed. But the revolutionary attitudes and aesthetics of these children of New York City were deeply connected to that position of marginalization and disenfranchisement. Particularly in the United States, where consumerism is tethered to cultural citizenship and social belonging, dress and self-fashioning took on a valence of agency, even if in small ways. Nameplate jewelry tells a story about the inextricable intersections between style and society, in which wearing one’s name for others to see is also a symbolic site of struggle over selfhood, sovereignty, and social belonging.

A foundational motivation for this book was encountering the lack of recorded and published history addressing this style of jewelry or its wearers. We reached out to jewelry historians and experts, inviting them to weigh in on their understanding of where nameplates came from. Several told us that nameplates did not have a history because, as some expressed, nameplates are not “fine jewelry”—a technical category for objects of adornment made from precious metals and gemstones that also serves as a euphemism for jewelry that is deemed significant due to the perceived value of the artistic or cultural tradition from which it comes. The complicated and stigmatized associations that nameplates sometimes contain are the central reason that their history has not yet been written, as many of the people who have created and worn them have long been denied respect, memorialization, and care.

The release of our podcast resulted in an invitation to write the first-ever academic article about nameplate jewelry, which was published in a special, fashion-focused issue of

QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking in 2017. But the process of researching and writing a long-form article for a scholarly outlet with a limited audience led us to realize that this subject warranted a more visual documentation than was possible with a podcast or an essay and, most important, a deeper, more personal exploration of why people find nameplates to be meaningful. We had learned so much from our interviews; what might be uncovered if the conversation was opened up to people from around the world?

Copyright © 2023 by Marcel Rosa-Salas and Isabel Attyah Flower. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.