Introduction

What is it that defines a home? Is it the perfectly chosen paint colors? The moldings, the archways, or the beams? Is it the matching nightstands, the puddled curtains, the tiled bathrooms, the oak-plank floors? For years, shelter magazines and design books defined a home that was worth having—and, by extension, a home that was worth showing off to the world—as one that was decorated just so, that paid attention to those kinds of details, and that was often brought to life by someone with professional expertise in such matters. And while those homes were often beautiful, they sometimes evoked an uneasy sense of anonymity; you got the same feeling from looking at them as you did from flipping through the catalog of a big-box furniture store. You wondered, “Who, exactly, lives here?”

When we founded our online magazine Sight Unseen more than a decade ago—with the mission to provide readers with a highly personal look at design objects and the creative people behind them—we made a conscious decision to approach interiors from a radically different point of view. We believed, and still do, that while layout and fixtures and fabrics can all play a part in making a space aesthetically pleasing, it’s the objects you surround yourself with that truly give your home its soul: the vintage Danish chair you found at a flea market, the indigo vase you bought from an LA ceramicist, the candlesticks a friend brought back from Mexico, the side table you’ve been saving up to buy from a designer you follow on Instagram. These objects are the story you tell to the world about your personality and your obsessions, your experiences and your memories, your desires and your intentions. Infused with your personal narrative, they provide a catalyst for conversation when friends visit (or virtually view) your home, and a comfort for when you’re cooped up inside, as so many of us were in recent years.

At the start of 2020, three weeks into quarantine, we got an email from a literary agent in New York asking if we might be interested in writing a book; stuck at home, people were looking for inspiration and new ways to think about their interiors. A Sight Unseen book was something we’d thought about—and been asked about—for years, but had never pursued, partly because the idea of putting together a compendium of our past stories, or our favorite homes and design studios, never really felt momentous enough to us. But the pandemic brought us a whole new perspective. When we thought about what we were collectively going through at the time, and how our objects were such a huge source of comfort in isolation, it became clear that we had to write this book:

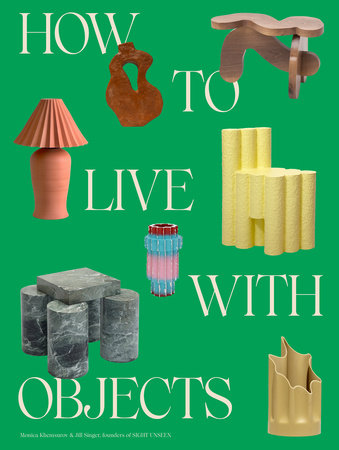

How to Live with Objects, a comprehensive guide to incorporating meaningful works of art and design into your home. The book would be expansive enough that its ideas could remain relevant for years to come, and it would allow us to combine all of our interests, and everything we’d learned over the course of our careers, into a single volume. The idea that you should accumulate, not decorate. The idea that opposing forces, like contemporary and vintage, ought to live in harmony in your space. The idea that it’s okay to think about your home not as something to be completed, but as a forever work in progress, in the same way that you yourself probably are. Plus, everything you’ve always wanted to know about objects: why they’re important, who makes them, what makes them valuable, how to acquire them, and, ultimately, how to put them together in a way that’s warm, inviting, and extremely personal—without a hefty budget or the help of an interior designer or decorator.

These ideas have always felt personal to us, because it was objects that paved the way for our interest in design. Neither of us studied design in school—we’re both trained as journalists— but both of us had formative experiences with design by way of the domestic items we grew up with. When Jill looks back on her suburban Midwestern childhood, she remembers the tulip-patterned Marimekko sheets, the wooden highboy engraved with yellow flowers, the lamp depicting a unicorn resting in a garden, and the sofa embroidered with tropical florals. Monica, growing up in Ohio, actually lived with some design classics, like Breuer’s Cesca and Wassily chairs. But as a lover of all things colorful and sparkly, her bedroom as a five-year-old consisted of wild Memphis-style sheets and a funny collection of Swarovski crystal animals that her dad brought her each time he came home from a work trip. These objects remain firmly implanted in our memories and represent the first time we experienced a strong emotional connection to our physical environment.

As a child, when you live with things someone else has chosen for you, you either don’t feel anything for them at all or you ascribe meaning to them via your imagination. Things also tend to hold more meaning when they act as your introduction to something, which is why your favorite album is often the first one you heard by that band, or why your first love sticks with you for so long. As you grow older, it’s important to keep intact the magic of those childhood things. If you can choose your objects with care, educating yourself about where they came from and making the experience of acquiring them part of the story—rather than, say, throwing a bunch of stuff into your cart as you browse a Target late at night—your relationship to objects can become exponentially more meaningful as you age.

At its core, that’s what this book is about, and it’s an idea we’ve been exploring ever since we founded Sight Unseen. In the early days, when we would visit one of our creative friends for the site’s popular At Home With column, we focused on objects partly out of necessity. We often couldn’t afford a photographer, and we weren’t adept enough image-makers to create the kind of perfect sweeping room views readers want to see in their home tours. But we were also inherently more interested in our subjects’ possessions than in how well coordinated their living rooms were. We’d ask them to show us their favorite books, or tell us more about the objects on their shelves that may have played a part in inspiring their work. We’d beg for the history behind architect Rafael de Cardenas’s vintage Ikea chair, or ask to peek inside the pages of creative director Joseph Magliaro’s Alessandro Mendini–designed

Casabella magazines. The goal of Sight Unseen has always been to tell the stories behind the stuff— both the things people have made and the things they’ve acquired—and that always felt like the best way to understand our subjects on a deeper level. Objects were the perfect conduit for our storytelling.

At the time of Sight Unseen’s founding in 2009, we were one of the only publications doing the work of demystifying the world of design for people outside the industry and focusing on the importance of objects and how they’re made. Design was still a niche interest when we started, one much lower on the totem pole of cultural relevance than fashion or art. Our friends working in those industries didn’t pay too much attention to what we were doing, nor did they really seem to understand it. But over the past decade, we’ve watched the world tilt in our direction. Provenance—the idea that knowing where something came from makes it inherently more valuable—was always a thing in the vintage furniture market, but it was around that time that people started to truly be interested in throwing back the curtain on all of the possessions they sought to acquire. This curiosity had its roots in the slow food movement, but it soon expanded to areas such as beauty, fashion, and contemporary design, with a raft of online magazines suddenly popping up to interrogate the building blocks of our closets, our medicine cabinets, and our domestic spaces.

It was probably social media, though, that created a perfect storm in terms of accelerating the personal style revolution and the ascendancy of design in popular culture. Instagram debuted not even a year after we started Sight Unseen, and people began obsessively documenting the world around them, then turned their cameras on their own homes. Social media is how a six-foot-tall, neon-pink Ettore Sottsass mirror went from being a luxury reserved for people like Karl Lagerfeld to a selfie spot at New York’s Opening Ceremony to the ultimate influencer accessory (and subject of a 2019

New York magazine profile). It’s how terrazzo took over the world, as people began posting photos of the floors beneath them on their travels, a look that soon translated into housewares and accessories. It’s how a series of previously under-the-radar archival chair designs—ranging from Mario Botta’s metal rollback Seconda to the spidery ’80s-era Ekstrem to Herman Miller’s gum-inspired Chiclet—became status symbols and household names. “To own one was to buy a new kind of social media bragging rights—a sign of in-the-know sophistication,” the fashion trade magazine

WWD wrote about the phenomenon.

Copyright © 2022 by Monica Khemsurov and Jill Singer, founders of Sight Unseen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.