IntroductionHistory, as nearly no one seems to know, is not merely something to be read. And it does not refer, merely, or even principally, to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. —James Baldwin,

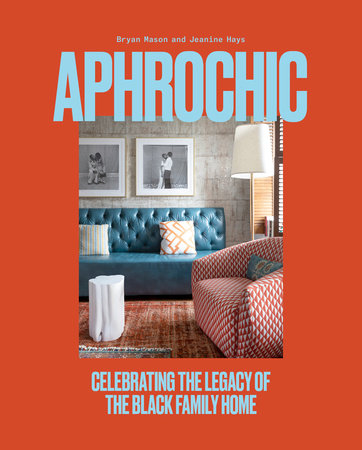

Dark Days We all have a story of home, beginning with the first place that we remember. It travels with us, growing as we grow, written into our homes with colors, patterns, furniture, and accessories. In our first book,

REMIX, we explored those elements and the ways that we use them in our homes to tell our story. In this book, we are excited to explore the story of home itself, those of the families featured here, and that of African Americans as a whole.

We at AphroChic are lovers of history. And while this is a design book, it’s also a book about history, for as James Baldwin points out, the past is always with us, and we are formed by both the parts we include and by what gets left out. For too long, the Black family home has been left out of the story of America—a missing character. It’s time to write the full story.

The Black family home is a vibe. More than just a place where people live, it’s a feeling. It comes from the food that we eat, the music we hear, the stories we share. It comes from the elders in our families—the ones who teach us to act right, be quiet, and pay attention. The ones with the stories, recipes, and lessons that we never forget. Whether an apartment, a condo or a house, a new-build, or a generational home, the feeling is the same. Home is like “soul”—indescribable, but you know it when you feel it and you miss it when it’s gone. Much of that feeling is carried in the unique aesthetic that defines African American design.

Like every part of a culture, design is shaped by history. The shape of American history has created a set of needs for African Americans, which are reflected in our homes. Much as we have with food, music, and dance, African Americans have used design as a way of meeting those needs. African American design is uniquely experiential in that it isn’t defined by look as much as it is by feel. There are no defined color palettes or furniture styles. Instead, it uses a diverse array of approaches to craft environments that evoke feelings such as safety, control, visibility, celebration, and memory. Each of these plays an important role in the feeling of home that these spaces convey. When asked what their homes mean to them, “safety” was the first response of every homeowner in this book. Life in America is not safe for Black people and never has been. While the sense of safety our homes provide is not the same as physical security, home is a respite from the psychological pressures of the outside world. For that reason, Black homes are filled with comfortable things and things that comfort.

Control, as an element of African American design, is about the ease with which our creative decisions are made. Home offers a space that doesn’t have to be carved out, contended for, or defended once won. It doesn’t ask us to explain ourselves, speak for our race, ignore its microaggressions, or be on call for teachable moments. No one ever asks to touch your home. In place of all that, home gives us the control we need to express and represent ourselves freely.

Visibility and representation are constant social battles for African Americans—as much a question of how and why we’re seen as when and where we are seen. Home is a place apart from the scrutiny and stereotypes of the white gaze. And if we struggle to separate who we are from how we are seen, designing our homes can give us the space and means to address those issues in ways that not only showcase our stories and cultures but celebrate them as well.

Celebration may be the most important element of African American interior design. We do not define our culture by tragedy and oppression but by enduring hope, creativity, and joy. The embrace of color, art, and culture in our design creates a joyful place where the stories of a person, a family, and a people are celebrated and remembered.

Memory is the root of soul, and a vital part of African American design. Through design we both retain the past and contemporize it. Our designs recall the places we grew up in, our ancestral homes and the ancestors themselves, connecting our stories to the stories that came before. Memory is where African American design starts.

Because of how well it blends eras and aesthetics, African American design is strongly anti-thematic, valuing personal expression above all else. Like jazz improvisations or street style fashion, our design aesthetics are unique to each of us—a multitude of expressions connected through a variety of experiences that are shared but not identical. Within these experiences, home may be where we go to feel safe, welcome, and seen, but getting there has been difficult.

Beginning with Emancipation—and even before—the African American journey to home has been a hard-fought road, and never a straight route. We have built communities that were burned or destroyed by white supremacists; owned land that was stolen or from which we were driven away; established legal protections against discriminatory practices, only to see those protections rolled back until today, resulting in the lowest rate of homeownership among African Americans since the 1960s. Nevertheless, our journey is etched into the history of America. Its peaks and valleys have come at some of this nation’s most crucial turning points. Because of that, it’s a useful way to measure the nation’s social, political, and economic steps, both forward and back. And yet, it’s a story that hasn’t really been told before now and it’s important to consider why.

“At this point we leave Africa,” Georg Hegel once wrote, “not to mention it again. For it is no historical part of the World; it has no movement or development to exhibit.” Remembered widely as one of the architects of modern Western philosophy—and less widely as a framer of modern racism—Hegel’s statement continues to shape popular notions about the place of Black people in history. The sentiment hasn’t lasted because it’s true; it lasts because it justifies actions and normalizes power relationships built on the lie of a biological racial hierarchy. It took time. Racism as we know it today is not ancient, but it didn’t form overnight. Maintaining it requires the work of generations. Creating it required the hard work of forgetting.

Forgetting is a complicated and difficult act. The erasure of an entire people from history demands more than ignoring the highlights of their past. The present must also be obscured through stereotypes, misrepresentations, and omissions. In its representations as part of Black life in America, the Black family home has been subjected to all three.

Copyright © 2022 by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.