IntroductionWhen I was seventeen years old, I ran away from home. College acceptance letters had just come in, and my mother, Jean, had torn into all of mine before I could come home from school that afternoon. I was so angry with her for opening my mail that I packed a bag in the middle of the night, took the car with the GPS, and drove from our house in Atlanta (where this story begins and ends) to Nashville (where my cousin Semi lived, four hours northwest). In the morning, when Jean saw that my bed was empty and my toothbrush gone, she called me, over and over. In my very first act of rebellion as her son, I didn’t pick up.

I remember that trip to Nashville distinctly because Semi and I cooked coq au vin together. By then, as an avid watcher of the Food Network, I had tried my hand at a variety of non-Korean dishes, mostly flash fries and quick pan sauces, but never a proper braise. It was liberating to braise chicken with red wine on Semi’s tiny stove, not least because that just wasn’t how we cooked back in Georgia. My mother’s Korean soups and stews were vociferously boiled, the meat made fall-apart tender in stainless-steel stock pots or burbling earthenware called ttukbaegi. Slow-cooked dishes in general were a whole new frontier for me and wouldn’t become a fixture in my home cooking until years later in New York, where I would eventually go to college, take an internship at the Cooking Channel, and buy a yellow Dutch oven with my first paycheck. But for now, at seventeen, tucked away in Semi’s Tennessee bachelorette pad, I tasted freedom for the first time in my life. A vast world of pleasures had opened up to me, pleasures that had, until then, been reserved for adults who get to cook whatever they want, however they want, in kitchens that aren’t ruled by their parents.

When I came home a few days later, Jean brushed it off, pretended it was a nonissue that I had run away. But she did bring it up at dinner that night: “So, did you have a good trip?” Even then I could tell that she was practicing her loosened grip on me, her second son, the one who never got into trouble. Over a plate of her kimchi fried rice, which she had made for my homecoming (and would continue to make for many homecomings to come), I told her how I had been feeling, paralyzed at that great nexus between childhood and adulthood. I ran away because I needed some space, I explained. Though I didn’t say it at the time, she knew what I really meant: I ran away because I needed some space from

her. This hurt my mother greatly, I could tell. But she smiled and nodded and listened anyway. Seeing that effort—and the hidden worry in her face—was enough to thaw my cold, ungrateful heart. I burst into tears and apologized.

In many ways, I feel that I’ve been running away from home my whole life. I’m only just now, as an adult, starting to slow down and find my way back to Atlanta, where I was born and raised, to understand its role in my overall story. After a lifetime of running around, I’ve come to appreciate the stillness of rootedness. It took spending more time, too, in the kitchen as a food writer and journalist, first as an editor for publications like Food Network online and

Saveur, and now as a columnist for

The New York Times, to make me realize that we can never really run away from who we are. Not easily, anyway. This lesson was expounded for me during the pandemic, when I moved back home for one year to work on this cookbook with my mother. I wanted to write down her recipes, but as I got deeper and deeper into the project, I came to the conclusion that my recipes are an evolution of her recipes, and the way I cook now is and will forever be influenced by the way she cooks. This book, then, tells the constantly mutating story of how I have come to understand my identity not just as Jean’s son, but also as someone who has always had to straddle two nations: the United States (where I’m from) and South Korea (where my mother is from). Too often I have felt the pangs of this tug of war: Am I Korean or am I American? Only recently have I been able to fully embrace that I am at once both and neither, and something else entirely: I am

Korean American.

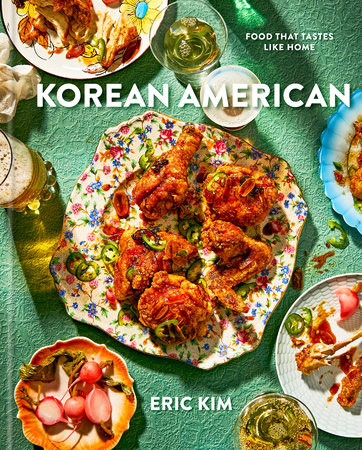

As is often the case with cooking, there are many answers to be found in the kitchen. The recipes in here explore that tension, and the ultimate harmony, between the Korean in me as well as the American in me, through the food my family grew up eating and the food I cook for myself now. At the end of the day, this is all, for me, food that tastes like home, from the Very Good Kimchi Jjigae (page 98) that fuels my weary soul to the Crispy Lemon-Pepper Bulgogi (page 240) that feeds my friends when they come over, or the Gochugaru Shrimp and Roasted-Seaweed Grits (page 40) I make for myself whenever I’m feeling especially homesick for Georgia, and for my mom. This book navigates not only what it means to be Korean American but how, through food and cooking, I was able to find some semblance of strength, acceptance, and confidence to own my own story.

This story is mine to be sure, and my family’s. But it’s also a story about the Korean American experience, one that in the history of this country is often never at the center. It’s about all the beautiful things that come with being different, and all the hard things that come with that, too. My hope is that in reading this book, you’ll see yourself in it, whether you’re Korean, Korean American, or neither, whether your family immigrated to Atlanta, Los Angeles, or Little Rock. Because at the heart of this book is really a story about what happens when a family bands together to migrate and cross oceans in search of a new home. It’s about what happens when, after so much traveling and fighting and hard work, you finally arrive.

There’s a pivotal moment that occurs whenever I’m on a long drive home from somewhere distant. The blurry picture starts to come into focus. I can let down my guard and turn off my GPS. The roads are familiar again. I don’t need a robot telling me about my own city, my own street, my own hometown. But sometimes, after that long drive, I’ll forget to turn off the GPS because my mind is wandering, or maybe I’m listening to a really good song or an especially juicy podcast. And as I roll into my mother’s driveway, eager to walk through those doors and crash into my old bed, it’ll talk back to me.

“Welcome home.”

Copyright © 2022 by Eric Kim. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.