CHAPTER 1

Past All DreamingIn December 2010, I was at a friend’s holiday party. I didn’t know many of the people there, and to ease my social anxiety, I was scanning the spines on the bookshelves when a song came up on the house speakers—one that sounded both entirely new to me and as familiar as my own skin. A woman was singing in a plaintive tone about “a place they call Lonesome,” where she hears the voice of her absent love speaking to her in “everything I see”— from a bird to a brook, “a pig or two,” to a “sort of a squirrel thing.”

Contextually, I couldn’t place the song. It possessed the openhearted, melodic feel of an old Carter Family recording, but there was also some gentle acoustic guitar fingerpicking that reminded me of Elizabeth Cotten, and harmonic movement that seemed to echo the songs of Hoagy Carmichael. The traditional elements seemed so finely stitched together, with such a sophisticated sensibility, that the whole sounded absolutely original—modern, even. The song swallowed me. The party froze. The room disappeared.

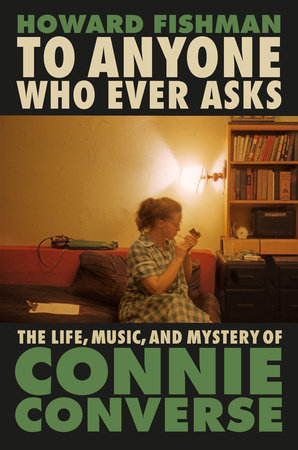

Eventually, I sought out the host, who smiled knowingly when I asked him what we were listening to. “Oh,” my friend said. “This is Connie Converse. She made these recordings in her kitchen in the 1950s, but she never found an audience for her music, and then one day she drove away and was never heard from again.” The name of the song was “Talkin’ Like You.”

On my way home that night, I stopped at a local record store that no longer exists and picked up a copy of

How Sad, How Lovely, the recently released album of Converse’s sixty-year-old recordings. Before going to bed, I cued up “Talkin’ Like You,” and listened to it a second time, now without any distraction.

Again, I heard the bluesy, spooky introduction, sung over an unusual series of seventh and diminished chords—placing it decidedly on the refined side of the popular music spectrum. The combination of the mysterious melody and complex harmony drew me back in, as did the song’s lyrics.

In between two tall mountains there’s a place they call LonesomeDon’t see why they call it LonesomeI’m never lonesome when I go there.I listened as Converse’s lilting, rolling guitar accompaniment followed, as the singer once again began her tale:

See that bird sittin’ on my windowsill?Well he’s sayin’ whipoorwill all the night through.Surely, this was a nod to the 1949 Hank Williams classic “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.”

Like the protagonist of Williams’s song, the whippoorwill keeps the narrator of “Talkin’ Like You” company when others will not.

See that brook runnin’ by my kitchen door?Well it couldn’t talk no more if it was you.The dispatch of her lover’s comeuppance begins, and then does not stop until the song finishes. The object of her affection will not talk to her? No matter; the water outside her door will.

Up that tree there’s sort of a squirrel thingSounds just like we did when we were quarreling.And there it was again. In a poetic leap, the singer identifies the curious sound she hears in a nearby tree as coming from “sort of a squirrel thing”— and sounds far more like a millennial than a young woman writing in the early 1950s.

In the yard I keep a pig or twoThey drop in for dinner like you used to do.Her ongoing traffic with nature continues. She keeps pigs, who join her for meals, the way her beloved does not or will not. The imagery could not be plainer: This person is no better than a pig, and she is perfectly happy to entertain other piglike comers if this one will not satisfy her needs.

I don’t stand in the need of companyWith everything I see talkin’ like you.Up that tree there’s sort of a squirrel thingSounds just like we did when we were quarrelingYou may think you left me all aloneBut I can hear you talk without a telephoneI don’t stand in the need of companyWith everything I see talkin’ like you.It is a bravura bit of songwriting, a lyric both empowering and entrancing. She doesn’t need anyone—neither their sympathy, nor their pity. We all want to be like this, all the time: self-assured, witty, happy, reliant on nobody and no one. Free. Listening to this song, I found it hard not to be captivated by this person, to want her as a friend, to know her.

Yet, as the rest of the album played, as I took in songs like “Playboy of the Western World,” “Father Neptune,” and “One by One,” the suspicions that had been vaguely floating in my consciousness began to harden into the only obvious conclusion: This “Connie Converse” character had to be a hoax, a gimmick. The songs were too fresh, too modern, too anachronistic to have been recorded in the 1950s. And even if they

had been recorded back then, someone surely would have discovered this person well before now. Music geeks like me would know about her, certainly, but more to the point: She was

so good that we would

all know about her.

These recordings didn’t sound like the music of a forgotten someone who was essentially doing a lesser-known version of what other people had gotten famous for—a Big Mama Thornton to Elvis Presley, an Eddie Lang to Django Reinhardt, a Barbecue Bob to Robert Johnson. As far as I knew, there was no one from the early 1950s on the other side of the Connie Converse equation, not remotely—not in the wide margins of the years that came before her and not in those that immediately followed. This music, if I were willing to suspend my disbelief, would exist out of time, out of music history altogether.

And the liner notes confirmed what my friend had told me: that Converse had literally vanished. Not like a J. D. Salinger, who retired from the public eye but then had continued writing in isolation. Not like a Terrence Malick or a Lee Bontecou or a Henry Roth—artists who stayed out of sight for decades before finally releasing new work. And not like a Captain Beefheart or a Su Tissue, musicians who’d walked away from their careers to do entirely other things. No. Like a Jimmy Hoffa. Like an Amelia Earhart. Gone.

Online searches revealed spare facts, including images of a woman who looked and dressed like one I might see in my Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood on any afternoon. The cat’s‑eye granny glasses, the shirtwaist dresses, the librarian hairstyle, the parlor guitar—it all smacked of a certain twee Brooklyn aesthetic that back then had already become a fad.

No, no, I thought.

No way.During my twenties and thirties, working as an independent musician, I’d come to know more than I’d ever wanted to about self-promotion. I was now forty, and only too familiar with the cleverness required to hook people’s attention—the spin, the reinvention, the PR stunts. I’d played that game. I knew the P. T. Barnum touch when I saw it.

“Connie Converse” was clearly some canny hipster who’d come up with a clever marketing campaign for her music. Someone who—when not in character—had cultivated impeccable vocal fry and was devoted to the films of Wes Anderson. Her long vintage dress was likely hiding a series of inexpensive flash tattoos. She’d devised a name with a nice classic ring to it, like “Lois Lane” or “Marjorie Morningstar”; created a noirish backstory about a disappearance; photoshopped some images of herself posing in thrift store attire to make them look like 1950s-era snapshots; and tried to pass off her own music as some kind of “lost” recordings made by this imaginary woman.

John Lurie had done something like this in 1999, with his album

The Legendary Marvin Pontiac: Greatest Hits, which was supposed to be the posthumously released lost recordings of a troubled musical genius who’d spent the last decades of his life in an insane asylum—though the album was actually Lurie and his pals having a bit of fun. “Connie Converse” was a Marvin Pontiac. She was not real. These were not old recordings newly discovered. She did not mysteriously disappear one day. There was no such person. She was a fiction. I was certain of it.

To satisfy my curiosity, I googled some more. Sure enough, I could find no news reports of a disappearance, no YouTube footage of Connie Converse performing, no reviews or accounts of her concerts, nothing at all related to her music that was contemporaneous with the time she was said to have been making it. All I could see was a handful of recent blog posts and articles related to the release of

How Sad, How Lovely—at which point the internet came to a dead stop.

Then, rereading the album’s liner notes, I noted a detail I’d overlooked—that Converse had served a stint as editor for something called the

Journal of Conflict Resolution. I went back online and, much to my chagrin, there it was: a 1968 essay called “The War of All Against All,” written by Elizabeth Converse, the journal’s managing editor.

Pause.

Could it be true? Was she actually real, and had she indeed written these songs—little earworms that sound like absolutely no one else—in virtual obscurity in the early 1950s, a time in American music often associated with the safe, inoffensive sounds of performers like Rosemary Clooney and Perry Como?

The more I listened to her music, the more my curiosity grew. I felt the need to know the rest of Converse’s story, the details that had driven her to make this particular music, at that particular time (if, indeed, she had). What had led to her tragic fate, to her simply vanishing (if that’s what actually happened to her). Who she was or, even, potentially, could still be.

And I found that my experience was not unique. From what I could see online, Converse had already begun to attract a cult of followers who were freaking out about her on social media and chat boards. Because so little about her was known, she seemed more myth than person, and as Greil Marcus wrote in

Mystery Train, “History without myth is surely a wasteland; but myths are compelling only when they are at odds with history.” This certainly seemed to be the case with Converse, someone upon whom we could project our own personal narratives and agendas, and no one could argue. She’d already been taken up as a cause by outsiders of many stripes—each of whom claimed her as one of their own.

I fell prey to this same tendency, the Rorschach inkblots of her recordings revealing characteristics I felt I had in common with her, for better or worse: outsize artistic ambition; vulnerability that lay protected beneath a hard veneer of willful self-reliance; a love of language; a disdain for conformity; a refusal to compromise; a desire to be understood; insatiable longing. Without knowing anything about Connie Converse other than what I heard in her music, I began to care about her. Extravagantly.

Had Converse’s songs other than “Talkin’ Like You” been mediocre or worse, had that song been the only real keeper she’d written and recorded, her story still would have been a fascinating one in the annals of American music, albeit a minor one. A young woman writing and recording her own songs in the 1950s, a DIY singer-songwriter back before such terms existed, might have interested scholars and music historians in a footnote sort of way.

But what I heard as I played these recordings again and again was far greater than that. The visionary, forward-looking quality of what Converse had been up to seemed to suggest the need to update the narrative of mid-twentieth-century American song altogether.

CHAPTER 2

“One by One”

If Converse’s musical catalogue, taken as a whole, is like some metaphorical message in a bottle cast off from the shores of a dull, homogenous time of which she wanted no part (and that wanted no part of her), her song “One by One” may be its unifying message. The lyrics are direct enough:

We go walking in the darkWe go walking out at nightAnd it’s not as lovers goTwo by two,To and fro,But it’s one by one—One by one,In the dark.We go walking out at nightAs we wander through the grassWe can hear each other passBut we’re far apart—Far apart,In the dark.We go walking out at night,With the grass so dark and tallWe are lost past recallIf the moon is down—And the moon is down.We are walking in the darkIf I had your hand in mineI could shineI could shineLike the morning sun,Like the sun.Converse crystallizes in song the feeling of disconnectedness of midcentury urban America, a trend that has exponentially increased to this day as the dominance of smartphones and social media has made us seem more than ever a nation of zombies cut off from one another and from ourselves (though it’s also arguable that we’re more connected than ever, only in worse ways).

According to the

How Sad, How Lovely liner notes, Converse had written and self-recorded her songs while living in New York City in the mid-1950s, at a time when new fissures in the bedrock of American culture and society were beginning to have devastating impacts, creating the anomie to which Converse was responding. Urban populations were exploding, middle-class families were moving to the suburbs, and children in smaller towns and rural areas were becoming the first generation in their families to go off to college. Communities were in flux. In places like Manhattan, it had become a common place experience for a single person to feel, and to be, alone amid millions of other human beings. Modernity, which was bringing about medical and scientific miracles at a rapid pace, also caused its share of collateral damage.

Copyright © 2023 by Howard Fishman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.