OvertureWhat It TakesWe cannot know for certain whether Sofie and Zanfir Solomon saw the celebrity when he returned, but we may presume they got word of his arrival soon enough. It was the bitter winter of 1899 and the couple were in their mid-thirties, married for sixteen years and raising a growing nest of children. Their home county, Vaslui, was a sparsely populated chunk of land in eastern Romania, containing just over 110,000 people, roughly 6,800 of them Jews like the Solomons, all of them struggling through a devastating recession. But even in the long, bleak nights, there was cause for excitement in the local Jewish community: The prodigal son was on his way.

“For months before, if you had put your ear to the ground, you might have heard the distant rumble of his approach, and Vaslui held not only its ear to the ground, but its breath,” wrote Marcus Eli Ravage, a Vasluiander of the Solomons’ era. “On the street, in the market, at the synagogue, we kept asking one another the one question, ‘When will he arrive?’ ” At last, the long-anticipated landsman rode a midnight train into town, and on his finely tailored frock coat lay the scarcely visible dust of a place the Solomons may have heard of but could barely imagine; a place where the laws of the Old World didn’t apply (perhaps even the laws of physics—given that it was on the other side of the world, it was said that people walked upside down there); a place where a Jew could be whatever he saw fit to be. “I had heard of people going to Vienna and Germany and Paris, and even to England for business or pleasure, but no one, to my knowledge, had ever gone to America of his own free will,” Ravage continued. And yet here was one of their own, back from fourteen years in what they called “Nev-York,” decked out in finery such as they’d never seen.

“The streets were lined with craning, round-eyed, tiptoeing Vasluianders, open-mouthed peasants, and gay-attired holiday visitors from neighboring towns who, having heard of the glory that had come to Vaslui, had driven in in their ox-carts and dog-carts to partake of it,” Ravage recalled. Perhaps Zanfir and Sofie and their nine-year-old daughter, Celia, were among the rubberneckers; if so, they would have been astounded by the man’s diamonds, his capacity to rattle off words in the alien tongue of English, and his trunkful of presents: “There were railways that were wound up like clocks and ran around in their tracks like real trains, and dancing negroes, and squawking dolls, and jews’-harps, and scores of other delights for the palate as well as the fancy,” Ravage reported. The returnee said he was working for the American government in a high post and, though he maintained a humble demeanor, he alluded to a significant fortune. Surely the Solomons heard tell of what happened when the man went to synagogue on Saturday: He received the honor of an aliyah—an opportunity to recite a blessing alongside the holy scrolls of the Torah—which came with the obligation to make a donation, and instead of the customary three or four francs, the man calmly offered 125 of them. “From that day on,” wrote Ravage, “Vaslui became a changed town.” Suddenly, it seemed like everyone had the notion to pack up and leave.

But wait. Was it true that, as one local with information from overseas said, the man was wildly exaggerating his success? Sure. Did Ravage later find out that this revered individual—whom he nicknamed Couza, a Romanian word denoting royalty—was actually a mere foreman in a bedspring factory, his wife a dressmaker, and his palatial New York estate just a fraction of a flat? Of course. Did any of that matter? Not one jot. “There was a country somewhere beyond the seas where a man was a man in spite of his religion and his origin,” mused Ravage. “Even if the informer were right, and Couza were a sham, America surely was no sham.” Perhaps we are to take the story as allegory; either way, the point stood: In the new Jerusalem they called the United States, you could make it just fine as a bullshitter.

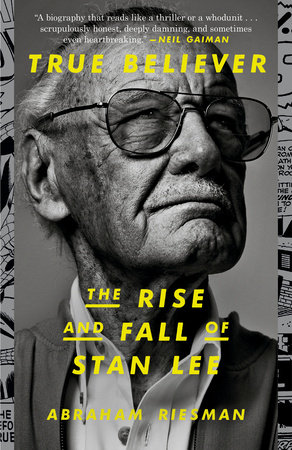

Sofie and Zanfir begat Celia. Celia and a man named Jack Lieber begat Stanley. Less famously, Celia and Jack also begat Larry, and that was it for their begetting. Stanley, as it turned out, sort of begat himself—he invented a character to play named Stan Lee and never got around to being Stanley again. The character is well known to myriad people in America and around the globe: a jovial, energetic man with a pedigree in comic books, bearing tinted glasses and a white mustache, bounding through the world with a gusto for life and community, spouting catchphrases (“Face front!” “’Nuff said!” “Excelsior!”) and winning the affections of both the young and the young at heart. But as the sun set on the year 2018, Stan was dead and Larry was the only living human who remembered what it was like before.

Before Spider-Man, before the Avengers, before the X-Men, before the Fantastic Four. Before Marvel Comics, before Atlas Comics, before Timely Comics. Before Stan Lee Media, before POW Entertainment, before those two companies were accused of defrauding their investors and prompting their employees to commit a menu of felonies. Before the movie cameos, before the mobile games, before the webisodes, before the straight-to-DVD movies that no one seemed to see. Before Stripperella, before the second coming of Stripperella. Before the elder-abuse allegations, before the sexual-assault allegations, before the 911 calls, before the comics signed in blood. Before the lawsuits, before the arrests, before the Supreme Court, before the guilty pleas. Before Jack Kirby, before Steve Ditko, before Peter Paul, before the Clintons (yes, those Clintons), before Gill Champion, before Jerry Olivarez, before Keya Morgan. Before Joan, before Jan, before JC. Before the name “Stan Lee” was trademarked, before it was signed away, before it was signed away again, before people started fighting over it like jackals at a bloodied wildebeest. Before everything was built, before it all fell apart. Before anything, there was Larry.

And after everything, there was still Larry. It had been forty-five days since Stan died just shy of age ninety-six. Larry, eighty-seven, sat on a beige couch in a breadbox-size studio apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, pants hiked up past his belly button and a green button-down covering his withered chest. The scene around Larry’s place was chaotic: papers piled atop a disused drawing board, boxes of miscellany lying haphazardly on the floor, a priceless personal sketch from the creators of Captain America yellowing in a cheap frame, a bedroom pillow bungee-corded to a computer chair for ergonomic purposes, pictures of dead women he once loved adorning nondescript shelving units. His goatee scraggled its way across the lower part of his face, and his eyes were mournful behind Coke-bottle lenses. He sighed.

“He had different sides to him,” Larry said of his late brother in the near-extinct New York Jewish accent the two of them had shared. “I feel like I’m almost talking about Charles Foster Kane. Who was he? What was he? What was he like?” Larry paused and pondered his own questions. His answer was simple, though entirely accurate: “It depends on who you talk to at what moment.”

By way of example, you could fast-forward a few weeks to a massive Stan Lee tribute show held at the famed Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. There, thousands of admirers waited in line to flash their tickets—the cheapest of them cost $150—and be admitted into the auditorium to see various entertainment professionals who knew or looked up to Stan talk about his impact on their lives. Outside, a fan mused on why he’d come. “I felt it was the best way to honor and celebrate the life of Stan Lee,” he said, “who in many ways shaped and formed the person I am today with all the comics and creations he made.” Another called Stan “the Mark Twain of Marvel” and said he belonged on a “Mount Rushmore of comic books.” Yet another said, “He’s an icon. You can’t beat Stan the Man. You can’t take that legacy away.” One well-wisher had driven all the way from Las Vegas, and with understandable cause: “For me, Stan Lee was actually pretty close to a father figure,” he said, “just because of growing up with his comics and everything. That’s how I learned a lot of my morality and got to connect on a deeper level with other people. I had a single mom, so it was nice to have a male person to look up to that I didn’t have in the household.” They waxed rhapsodic about his narratives, his interactions with fans, and his plentiful appearances in dozens upon dozens of superhero movies, where he’d pop in to offer wisdom or comic relief, often both at the same time. To these people, Stan had been an inspiration, something close to a god.

Copyright © 2020 by Abraham Riesman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.