Prologue On October 27, 2018, a gunman burst into a Pittsburgh synagogue and killed eleven people. Within hours, the global Jewish community mobilized into action. Jews across the world raised money to cover funeral costs. Rallies and memorials were held in every major city. The global Jewish community expressed public sympathy and outrage, while volunteers flocked to Pittsburgh to serve the community hot meals and attend the funerals. The message was clear: An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us.

In general, the global queer community does not respond like this in times of crisis. On January 14, 2019, just two and a half months after the synagogue shooting, news broke that a new wave of queer “purges” were taking place in Chechnya, a small Russian republic. Forty queer people were detained and two were killed. But there was no effective global call to action. Between October 27 and January 14, at least three Black trans women were murdered in the United States. As usual, the epidemic of violence against Black trans women did not prompt any kind of unified or helpful communal outrage.

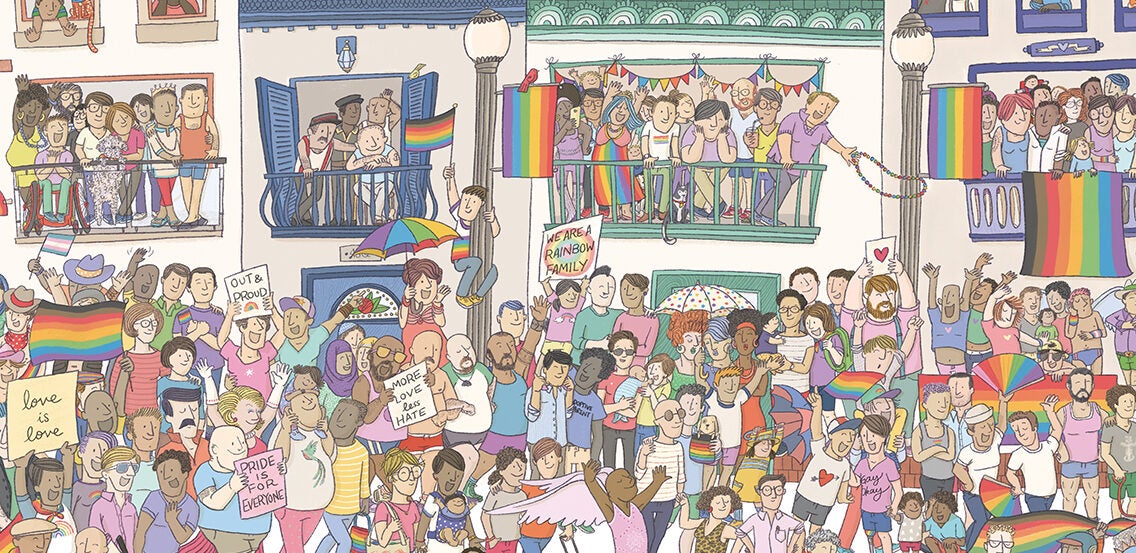

As a queer Jew, I watched these attacks on my two communities unfold parallel to each other. Distraught, I thought of a quote from the Talmud, a piece of ancient Jewish scripture, that says, “All Jewish people are responsible for one another.” We don’t always get it right, but the importance of showing up for other Jews has been carved into the DNA of what it means to be Jewish. It is my dream that queer people develop the same ideology—what I like to call a Global Queer Conscience. The Global Queer Conscience is an attitude that repositions how we see ourselves as queer people and how we fit into the world.

I cannot, and will not, speak for the community at large—no one person can. But I believe that this dream will become reality if we come to this simple understanding:

Queer people anywhere are responsible for queer people everywhere.

The New Queer Conscience I wish someone had told me that being queer means you are never alone. It is 10:15 p.m. I am sixteen years old and in the worst pain of my life. I am in love with my straight best friend. I am standing at a party in total shock as he gives me a play-by-play of his first hookup with his new girlfriend. I act curious and excited, demanding all the details.

At some point, I grab his shoulder, eager for any kind of contact with him. He shrugs me off, and I disappear toward the train home.

My heart rate rises. I can no longer speak. I’m standing at the train station. Flashes of our conversation: his face, her hands, his zipper. I double over clutching my stomach. I tell myself, as I always I do, that if I replay the scene in my mind it will eventually hurt less.

Pulse, mind, and tears racing, I’m sure she doesn’t see his beauty the way I do. But a wave of nausea and pain forces me to refocus. Her hand, his Abercrombie & Fitch jeans, a zipper . . . and blackout.

The next day in algebra he throws me an encouraging wink as our teacher distributes a midterm. An unintentional kick to the stomach. I flee to the bathroom and lock the door.

Big picture, I don’t know anyone queer who can tell me that these feelings are normal. And from a practical perspective, nobody can tell me anything because I just locked myself in the bathroom.

So, I turn on the tap and speak to myself. I look in the mirror and say out loud, for the first time, “Adam Eli, you are gay . . .” I let that sentence echo a little in the bathroom, for the drama. Then I hear words not of my making, but out loud, in my own voice, address the mirror:

“. . . and it’s going to be okay.”

What does queer mean?

I am gay because I primarily experience same-sex attraction, and, by my own definition, that also makes me queer. Many people have their own definition of what queer means, and one is no more valid than another, but here is mine:

Queer: different, or other

If there are three blue chairs and one pink chair—the pink chair is queer. Queerness only exists in opposition to what’s perceived as “normal.” When it comes to gender and sexuality, our society’s “normal” is defined by one cisgender man and one cisgender woman who experience opposite-sex attraction and live comfortably in their gender roles. If you deviate from any part of that norm, welcome and pull up a seat. In my book, you are queer!

When describing our community, I always say LGBTQIAA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual, ally, plus). The most important of these symbols is the plus sign. The plus sign opens the door for everyone. Perhaps you do not identify with any of these letters. Perhaps how you feel or how you are has not been verbalized to the world yet. You are loved, and you are welcome here.

The word

queer and the community it describes are both evolving—and that’s a good thing. I hope our community continues to expand and becomes more inclusive in ways that I cannot predict. I imagine, and hope, that one day my definition will be outdated.

When I was younger, I knew I was different because all my interests were “meant for” girls. I was obsessed with Disney princesses and had a huge crush on Leonardo DiCaprio in

Titanic. If I could have pressed a button to become more like my female friends, I would have in a heartbeat.

I was resentful and confused. Uncomfortable with boys and forbidden to be one of the girls, I existed in the margins, in a space between spaces.

Copyright © 2020 by Adam Eli; Illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.