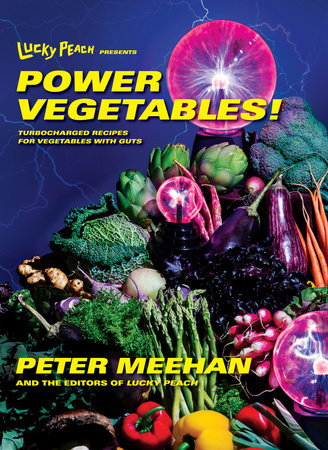

Mostly vegetarian and infrequently vegan, the recipes in Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables! are all indubitably delicious.

The editors of Lucky Peach have colluded to bring you a portfolio of meat-free cooking that even carnivores can get behind. Designed to bring BIG-LEAGUE FLAVOR to your WEEKNIGHT COOKING, this collection of recipes, developed by the Lucky Peach test kitchen and chef friends, features trusted strategies for adding oomph to produce with flavors that will muscle meat out of the picture.

The editors of Lucky Peach have colluded to bring you a portfolio of meat-free cooking that even carnivores can get behind. Designed to bring BIG-LEAGUE FLAVOR to your WEEKNIGHT COOKING, this collection of recipes, developed by the Lucky Peach test kitchen and chef friends, features trusted strategies for adding oomph to produce with flavors that will muscle meat out of the picture.

“A vegetable cookbook like no other, in a good way.”

—The New York Times

One of “Fall's 6 Best Food Books”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Lucky Peach’s Power Vegetables is the Van Halen air guitar solo of plant-centric cooking... Lifelong herbivores, skeptics who cohabitate with vegetarians, and omnivores looking to diversify their repertoires will benefit from the bold fare in Power Vegetables, spanning from zucchini pizza, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie (spoiler: it’s lamb-free!), and this vibrantly photogenic borscht.”

—USA Today

“As with so much of what Lucky Peach does, the balance between irreverence and utter seriousness of purpose makes this book a delight. The playful visuals and Meehan’s off-the-cuff text offer near-constant reminders that vegetables are wildly versatile, and cooking them ought to be fun.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Peter Meehan (and the editors of Lucky Peach) found a way to make a vegetable cookbook that you'll want to read as much as you want to (lick the pages) cook from.”

—Food52.com

“Aggressively tasty vegetables”

—NYTimes.com

“The indie food magazine Lucky Peach has made our dreams come true with their new cookbook Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!: Turbocharged Recipes for Vegetables With Guts, in which the editors of the quarterly mag share all the best vegetable-focused dishes from our favorite chefs and restaurants—including the legendary ABC Kitchen's Squash Toast.”

—MindBodyGreen.com

“An exuberant take on vegetables” and one of “Our Top 10 Cookbooks for 2016”

—Newsday

“The editors of Lucky Peach, a quarterly food magazine founded by former NYT restaurant critic Peter Meehan and chef Momofuku’s David Chang, are on a mission to add a little boom boom pow to your weeknight cooking. This assortment of meat-free meals moves beyond pasta and grain bowls, putting produce front and center with help from guest contributors like Chang, Jessica Koslow of Sqirl, and Brooks Headley and Julia Goldberg of Superiority Burger.”

—InStyle

“A raucous pileup of umami-stoked veggies photographed with kitschy action figures. The recipes are easy and accessible...”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Any book with an exclamation point in its title promises to be a good time, and the third book from the Lucky Peach editors doesn’t disappoint. They switch gears after their previous meat-centric cookbook with 100-plus recipes that show vegetables are anything but boring, like tempura green beans with honey mustard and bright, charred carrots.”

—TastingTable.com

“Proof that vegetables are cool: They’re getting the Lucky Peach treatment.”

—The Washington Post

“The humorous and diverse roster of recipes from top chefs including Ivan Orkin, David Chang and Jessica Koslow is made far less intimidating by witty commentary, quick Q & A’s and detailed instructions that feel as if your very talented, very cool chef friend is teaching you some cherished industry secrets.”

—PasteMagazine.com

“The idea that vegetables can make up a full, satisfying meal is no longer a novel concept... But now cooking weekday meals with this emphasis just got a whole lot easier, thanks to a new cookbook from Lucky Peach. And as its title, Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!, suggests, there are no weak links or dribble-y leeks to be found here.”

—Vogue.com

“If any publication is going to make cooking vegetables fun, it’s Lucky Peach. Plus, chefs such as Ivan Orkin and Brooks Headley contributed recipes.”

—GrubStreet.com

“Lots of brightly colored graphics and photographs that are themselves mostly fun and a bit silly (one shows blue cheese dressing for a wedge salad also being poured over toy trucks and shoes), as well as recipes that one could say the same thing about: daikon with X.O. sauce, foil-wrapped vegetables, Kung Pao celeries, miso butterscotch.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Meehan and his fellow editors at Lucky Peach magazine have produced a book of entirely charismatic vegetable dishes. Readers will find the likes of Buffalo cucumbers, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie, Sichuan squash stew, and zucchini mujadara, along with input from hotshot chefs such as David Chang and Ivan Orkin.”

—Boston Globe

—The New York Times

One of “Fall's 6 Best Food Books”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Lucky Peach’s Power Vegetables is the Van Halen air guitar solo of plant-centric cooking... Lifelong herbivores, skeptics who cohabitate with vegetarians, and omnivores looking to diversify their repertoires will benefit from the bold fare in Power Vegetables, spanning from zucchini pizza, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie (spoiler: it’s lamb-free!), and this vibrantly photogenic borscht.”

—USA Today

“As with so much of what Lucky Peach does, the balance between irreverence and utter seriousness of purpose makes this book a delight. The playful visuals and Meehan’s off-the-cuff text offer near-constant reminders that vegetables are wildly versatile, and cooking them ought to be fun.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Peter Meehan (and the editors of Lucky Peach) found a way to make a vegetable cookbook that you'll want to read as much as you want to (lick the pages) cook from.”

—Food52.com

“Aggressively tasty vegetables”

—NYTimes.com

“The indie food magazine Lucky Peach has made our dreams come true with their new cookbook Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!: Turbocharged Recipes for Vegetables With Guts, in which the editors of the quarterly mag share all the best vegetable-focused dishes from our favorite chefs and restaurants—including the legendary ABC Kitchen's Squash Toast.”

—MindBodyGreen.com

“An exuberant take on vegetables” and one of “Our Top 10 Cookbooks for 2016”

—Newsday

“The editors of Lucky Peach, a quarterly food magazine founded by former NYT restaurant critic Peter Meehan and chef Momofuku’s David Chang, are on a mission to add a little boom boom pow to your weeknight cooking. This assortment of meat-free meals moves beyond pasta and grain bowls, putting produce front and center with help from guest contributors like Chang, Jessica Koslow of Sqirl, and Brooks Headley and Julia Goldberg of Superiority Burger.”

—InStyle

“A raucous pileup of umami-stoked veggies photographed with kitschy action figures. The recipes are easy and accessible...”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Any book with an exclamation point in its title promises to be a good time, and the third book from the Lucky Peach editors doesn’t disappoint. They switch gears after their previous meat-centric cookbook with 100-plus recipes that show vegetables are anything but boring, like tempura green beans with honey mustard and bright, charred carrots.”

—TastingTable.com

“Proof that vegetables are cool: They’re getting the Lucky Peach treatment.”

—The Washington Post

“The humorous and diverse roster of recipes from top chefs including Ivan Orkin, David Chang and Jessica Koslow is made far less intimidating by witty commentary, quick Q & A’s and detailed instructions that feel as if your very talented, very cool chef friend is teaching you some cherished industry secrets.”

—PasteMagazine.com

“The idea that vegetables can make up a full, satisfying meal is no longer a novel concept... But now cooking weekday meals with this emphasis just got a whole lot easier, thanks to a new cookbook from Lucky Peach. And as its title, Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!, suggests, there are no weak links or dribble-y leeks to be found here.”

—Vogue.com

“If any publication is going to make cooking vegetables fun, it’s Lucky Peach. Plus, chefs such as Ivan Orkin and Brooks Headley contributed recipes.”

—GrubStreet.com

“Lots of brightly colored graphics and photographs that are themselves mostly fun and a bit silly (one shows blue cheese dressing for a wedge salad also being poured over toy trucks and shoes), as well as recipes that one could say the same thing about: daikon with X.O. sauce, foil-wrapped vegetables, Kung Pao celeries, miso butterscotch.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Meehan and his fellow editors at Lucky Peach magazine have produced a book of entirely charismatic vegetable dishes. Readers will find the likes of Buffalo cucumbers, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie, Sichuan squash stew, and zucchini mujadara, along with input from hotshot chefs such as David Chang and Ivan Orkin.”

—Boston Globe

INTRODUCTION

I like a lot of vegetable cookbooks, so when we decided to make one ourselves, it meant I had to think about how to approach vegetable cookery from a Lucky Peach perspective.

I didn’t want to tell you to cook with what’s in season (you have already been told to do this) or to treat your beautiful in-season vegetables simply (ditto). I didn’t want to put together a vegetable/vegetarian cookbook for its explicit healthfulness or wholesomeness, though I appreciate and welcome those qualities in any dish, vegetable or not.

I wanted the book to be 98% fun and 2% stupid. I wanted something that took the sweaty, anxious what-are-we-going-to-eat-this-week feeling that sometimes casts a shadow over a Sunday trip to the supermarket and answered it, yelling WE ARE GOING TO EAT VEGETABLES AND THEY ARE GOING TO BE AWESOME.

Look, when I come home from work to a bowl of rice and some steamed broccoli and maybe a little jarred Chinese chili crisp, I’m a happy camper. But sometimes you need more: You need vegetables that are going to be exciting, that will push easy meat- or carb-centric dishes out of the spotlight. Which means they need to be what?

Powerful.

So I knew what we needed. And by that point in the book-making process not only did I want an exclamation point at the end of the title, I was thinking in all caps. Thinking meaningless success-o-slogans like FLAVOR IS POWER and EASE IS POWER and SIZE IS POWER and FIRE IS POWER and POWER IS POWER. I wanted weeknight all-caps cooking for people looking to eat more vegetable-centered meals.

What is all-caps cooking? It means center-of-the-meal dishes or certainly center-of-attention cooking. Elote—a Mexican way of gussying up corn on the cob (see page 156)—is a perfect example of a side dish or an appetizer in the Power Vegetables! style. Regardless of what you’ve got on the menu at your grill-out, you’re not going to have leftover elote, and if I’m there I’m probably gonna fill up on them and neglect the burgers.

It means vegetable dishes with real flavor. Flavorfulness is subjective, and it alone does not translate into power. There were any number of dishes that we tasted in the making of the book that we’d eat and enjoy and then sit there looking at, asking the question: But are you powerful, little plate of vegetables? And in that moment, there were many delicious things that were then either cast aside or amped up. For me, pappa al pomodoro was too plain, but pappa al pomodoro crossed with English muffin toaster pizzas (see page 136) gave my cerebellum the right amount of tingle. Traditional vichyssoise barely squeaked by—it’s almost too simple—but a variation on vichyssoise made with dashi (see page 138) is clearly a PV.

The idea of what constituted a power vegetable mutated over time. The original over-the-top subtitle I had in mind for this book was: “102 turbo-charged recipes that will push the meat off your plate—except for the meat that’s in them!”

See, I originally conceived of meaty vegetable dishes standing shoulder-to-shoulder with naturally vegetarian or vegan ones. But as we started to test and sort and select, I thought about what I really wanted to be eating. (I would say “what people who buy this book want to be eating,” but I can’t really judge your situation/needs/wants, since you are, at this moment, a fictional, collective construct propelling this introduction.) And that is why what I thought constituted a power vegetable when we set this ship out to sail is different from what I do here on the shore we’ve landed on. How so?

The biggest and most important change is that meat is gone—terrestrial flesh, at least. (There is passing mention of optional bacon in a couple of places; because it is bacon, I felt like that was okay.) But you’ll have to pry anchovies and their umami-rich brethren from my cold, dead hands.

There were dishes where this mattered more than I thought it would, like mapo tofu, which really gets a lot of power from the little bit of meat that is usually in it, which meant it was just more work than we anticipated to get our mushroom-based version (see page 132) up to par. There were dishes where I thought I’d miss it, like the French Onion Soup (page 126), and it turns out it was the vegetables making the dish delicious all along, like that story about Jesus and one set of footprints on a beach, and the onions are Jesus.

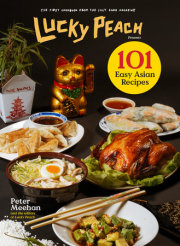

I thought that after we published 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I’d let myself relapse into the old Lucky Peach way of running impenetrable-but-interesting cheffy recipes, at least for some portion of the book. We’d examine Jeremy Fox’s influential Green Peas in White Chocolate or investigate how to put together a gargouillou à la Michel Bras or maybe dig out Roxanne Klein and Charlie Trotter’s catalog of high-end raw food cooking. But it came down to the same question: Is that really what we’re going to eat at home, what we’re going to cook? Is that where the POWER in VEGETABLES is?

I’ll go yes and no on that. If you have the means, the time, and the talent, there’s a lot to be said for advanced vegetable manipulation: how textures can be twisted, how flavors can be layered, how the composition of a dish can affect how it eats. But at home, how often are you or how often am I going to make that kind of food? I want you to be cooking from this book, preferably all the time. We have borrowed many of the recipes here from chef friends/acquaintances/ crushes, but we’ve focused on their most doable work, not their most refined.

Instead you will notice there are four spots in the book where we stop with the relentless recipeness of it all and talk to some chefs about what a power vegetable is to them. David Chang, Brooks Headley, Julia Goldberg, Jessica Koslow, and Ivan Orkin all weigh in.

Chef-sourced or otherwise, we’ve tried to make and keep the recipes easy. EASE IS POWER, after all, because what is more powerful than being able to turn ingredients into a desirable dinner with minimal effort? Almost nothing.

And with 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I learned that readers like knowing the rules of engagement up front. In that book, we did no frying, for example, and banished subrecipes. In these pages, we’ve allowed ourselves to wade into the hot oil a little more often, and subrecipes have been let in as long as they behave themselves and don’t have you jumping all over the book. The specific limitations we put on ourselves for this collection include:

1. NO PASTA RECIPES

I love pasta sooooooooo much. Too much? Maybe. What I’ve found over the years is that at home we’ll turn vegetables into a pasta sauce as a de facto option. I wanted this to be a slate of recipes that would give me new ideas for dinner and keep me from carbo-loading when I’m not eating meat. That said, nearly everything in here, or some form of its leftovers, would be eatable over pasta.

2. NO EGG-ON-IT DISHES; NO GRAIN BOWLS

There is nothing more in vogue at the time that this book is going to press than a bowl of some kind of grain—rice or quinoa or what have you—topped with some vegetables and pickles, crowned with a runny egg. And while we probably could’ve filled twenty pages of this book with thoughts on them, they’re kind of in the same class as pasta: You can put nearly any dish (or leftovers of any dish) from this book on a bowl of grains, nestle some appealing pickles in there and opt in to a runny egg if you like, and you will be stoked and well fed. But I’m not sure you need us to tell you much more about it.

3. FISH AND DAIRY ARE OKAY WITH US

After kicking meat out of the book, I was confronted with a choice: Should this be a 100% vegetarian or vegan book? For Power Vegetables!, I felt that the answer had to be no. Most of the vegetarians in my life eat fish. (I know that technically makes them “pescatarians,” but the number of people who self-identify with that term has to be statistically tiny.) Most eat dairy. And this isn’t a book exclusively for those who shun meat—if anything, I’m approaching it as an omnivore who wants things to be delicious first and foremost. But as with climate change, there’s no denying that the modern diet leans too heavily on meat and wheat, so it’s good to mix things up.

4. FRUITS ARE VEGETABLES

What, did you want the book to be all potatoes? As any six-year-old can tell you, cucumbers and tomatoes and squash and things with seeds in them are not vegetables. We are saying this to the six-year-old, “Pipe down, honey, we’re trying to get dinner on the table.”

Okay. That’s it. This is and these are POWER VEGETABLES!

pfm

I like a lot of vegetable cookbooks, so when we decided to make one ourselves, it meant I had to think about how to approach vegetable cookery from a Lucky Peach perspective.

I didn’t want to tell you to cook with what’s in season (you have already been told to do this) or to treat your beautiful in-season vegetables simply (ditto). I didn’t want to put together a vegetable/vegetarian cookbook for its explicit healthfulness or wholesomeness, though I appreciate and welcome those qualities in any dish, vegetable or not.

I wanted the book to be 98% fun and 2% stupid. I wanted something that took the sweaty, anxious what-are-we-going-to-eat-this-week feeling that sometimes casts a shadow over a Sunday trip to the supermarket and answered it, yelling WE ARE GOING TO EAT VEGETABLES AND THEY ARE GOING TO BE AWESOME.

Look, when I come home from work to a bowl of rice and some steamed broccoli and maybe a little jarred Chinese chili crisp, I’m a happy camper. But sometimes you need more: You need vegetables that are going to be exciting, that will push easy meat- or carb-centric dishes out of the spotlight. Which means they need to be what?

Powerful.

So I knew what we needed. And by that point in the book-making process not only did I want an exclamation point at the end of the title, I was thinking in all caps. Thinking meaningless success-o-slogans like FLAVOR IS POWER and EASE IS POWER and SIZE IS POWER and FIRE IS POWER and POWER IS POWER. I wanted weeknight all-caps cooking for people looking to eat more vegetable-centered meals.

What is all-caps cooking? It means center-of-the-meal dishes or certainly center-of-attention cooking. Elote—a Mexican way of gussying up corn on the cob (see page 156)—is a perfect example of a side dish or an appetizer in the Power Vegetables! style. Regardless of what you’ve got on the menu at your grill-out, you’re not going to have leftover elote, and if I’m there I’m probably gonna fill up on them and neglect the burgers.

It means vegetable dishes with real flavor. Flavorfulness is subjective, and it alone does not translate into power. There were any number of dishes that we tasted in the making of the book that we’d eat and enjoy and then sit there looking at, asking the question: But are you powerful, little plate of vegetables? And in that moment, there were many delicious things that were then either cast aside or amped up. For me, pappa al pomodoro was too plain, but pappa al pomodoro crossed with English muffin toaster pizzas (see page 136) gave my cerebellum the right amount of tingle. Traditional vichyssoise barely squeaked by—it’s almost too simple—but a variation on vichyssoise made with dashi (see page 138) is clearly a PV.

The idea of what constituted a power vegetable mutated over time. The original over-the-top subtitle I had in mind for this book was: “102 turbo-charged recipes that will push the meat off your plate—except for the meat that’s in them!”

See, I originally conceived of meaty vegetable dishes standing shoulder-to-shoulder with naturally vegetarian or vegan ones. But as we started to test and sort and select, I thought about what I really wanted to be eating. (I would say “what people who buy this book want to be eating,” but I can’t really judge your situation/needs/wants, since you are, at this moment, a fictional, collective construct propelling this introduction.) And that is why what I thought constituted a power vegetable when we set this ship out to sail is different from what I do here on the shore we’ve landed on. How so?

The biggest and most important change is that meat is gone—terrestrial flesh, at least. (There is passing mention of optional bacon in a couple of places; because it is bacon, I felt like that was okay.) But you’ll have to pry anchovies and their umami-rich brethren from my cold, dead hands.

There were dishes where this mattered more than I thought it would, like mapo tofu, which really gets a lot of power from the little bit of meat that is usually in it, which meant it was just more work than we anticipated to get our mushroom-based version (see page 132) up to par. There were dishes where I thought I’d miss it, like the French Onion Soup (page 126), and it turns out it was the vegetables making the dish delicious all along, like that story about Jesus and one set of footprints on a beach, and the onions are Jesus.

I thought that after we published 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I’d let myself relapse into the old Lucky Peach way of running impenetrable-but-interesting cheffy recipes, at least for some portion of the book. We’d examine Jeremy Fox’s influential Green Peas in White Chocolate or investigate how to put together a gargouillou à la Michel Bras or maybe dig out Roxanne Klein and Charlie Trotter’s catalog of high-end raw food cooking. But it came down to the same question: Is that really what we’re going to eat at home, what we’re going to cook? Is that where the POWER in VEGETABLES is?

I’ll go yes and no on that. If you have the means, the time, and the talent, there’s a lot to be said for advanced vegetable manipulation: how textures can be twisted, how flavors can be layered, how the composition of a dish can affect how it eats. But at home, how often are you or how often am I going to make that kind of food? I want you to be cooking from this book, preferably all the time. We have borrowed many of the recipes here from chef friends/acquaintances/ crushes, but we’ve focused on their most doable work, not their most refined.

Instead you will notice there are four spots in the book where we stop with the relentless recipeness of it all and talk to some chefs about what a power vegetable is to them. David Chang, Brooks Headley, Julia Goldberg, Jessica Koslow, and Ivan Orkin all weigh in.

Chef-sourced or otherwise, we’ve tried to make and keep the recipes easy. EASE IS POWER, after all, because what is more powerful than being able to turn ingredients into a desirable dinner with minimal effort? Almost nothing.

And with 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I learned that readers like knowing the rules of engagement up front. In that book, we did no frying, for example, and banished subrecipes. In these pages, we’ve allowed ourselves to wade into the hot oil a little more often, and subrecipes have been let in as long as they behave themselves and don’t have you jumping all over the book. The specific limitations we put on ourselves for this collection include:

1. NO PASTA RECIPES

I love pasta sooooooooo much. Too much? Maybe. What I’ve found over the years is that at home we’ll turn vegetables into a pasta sauce as a de facto option. I wanted this to be a slate of recipes that would give me new ideas for dinner and keep me from carbo-loading when I’m not eating meat. That said, nearly everything in here, or some form of its leftovers, would be eatable over pasta.

2. NO EGG-ON-IT DISHES; NO GRAIN BOWLS

There is nothing more in vogue at the time that this book is going to press than a bowl of some kind of grain—rice or quinoa or what have you—topped with some vegetables and pickles, crowned with a runny egg. And while we probably could’ve filled twenty pages of this book with thoughts on them, they’re kind of in the same class as pasta: You can put nearly any dish (or leftovers of any dish) from this book on a bowl of grains, nestle some appealing pickles in there and opt in to a runny egg if you like, and you will be stoked and well fed. But I’m not sure you need us to tell you much more about it.

3. FISH AND DAIRY ARE OKAY WITH US

After kicking meat out of the book, I was confronted with a choice: Should this be a 100% vegetarian or vegan book? For Power Vegetables!, I felt that the answer had to be no. Most of the vegetarians in my life eat fish. (I know that technically makes them “pescatarians,” but the number of people who self-identify with that term has to be statistically tiny.) Most eat dairy. And this isn’t a book exclusively for those who shun meat—if anything, I’m approaching it as an omnivore who wants things to be delicious first and foremost. But as with climate change, there’s no denying that the modern diet leans too heavily on meat and wheat, so it’s good to mix things up.

4. FRUITS ARE VEGETABLES

What, did you want the book to be all potatoes? As any six-year-old can tell you, cucumbers and tomatoes and squash and things with seeds in them are not vegetables. We are saying this to the six-year-old, “Pipe down, honey, we’re trying to get dinner on the table.”

Okay. That’s it. This is and these are POWER VEGETABLES!

pfm

Copyright © 2016 by Peter Meehan and the editors of Lucky Peach. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

About

Mostly vegetarian and infrequently vegan, the recipes in Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables! are all indubitably delicious.

The editors of Lucky Peach have colluded to bring you a portfolio of meat-free cooking that even carnivores can get behind. Designed to bring BIG-LEAGUE FLAVOR to your WEEKNIGHT COOKING, this collection of recipes, developed by the Lucky Peach test kitchen and chef friends, features trusted strategies for adding oomph to produce with flavors that will muscle meat out of the picture.

The editors of Lucky Peach have colluded to bring you a portfolio of meat-free cooking that even carnivores can get behind. Designed to bring BIG-LEAGUE FLAVOR to your WEEKNIGHT COOKING, this collection of recipes, developed by the Lucky Peach test kitchen and chef friends, features trusted strategies for adding oomph to produce with flavors that will muscle meat out of the picture.

Praise

“A vegetable cookbook like no other, in a good way.”

—The New York Times

One of “Fall's 6 Best Food Books”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Lucky Peach’s Power Vegetables is the Van Halen air guitar solo of plant-centric cooking... Lifelong herbivores, skeptics who cohabitate with vegetarians, and omnivores looking to diversify their repertoires will benefit from the bold fare in Power Vegetables, spanning from zucchini pizza, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie (spoiler: it’s lamb-free!), and this vibrantly photogenic borscht.”

—USA Today

“As with so much of what Lucky Peach does, the balance between irreverence and utter seriousness of purpose makes this book a delight. The playful visuals and Meehan’s off-the-cuff text offer near-constant reminders that vegetables are wildly versatile, and cooking them ought to be fun.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Peter Meehan (and the editors of Lucky Peach) found a way to make a vegetable cookbook that you'll want to read as much as you want to (lick the pages) cook from.”

—Food52.com

“Aggressively tasty vegetables”

—NYTimes.com

“The indie food magazine Lucky Peach has made our dreams come true with their new cookbook Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!: Turbocharged Recipes for Vegetables With Guts, in which the editors of the quarterly mag share all the best vegetable-focused dishes from our favorite chefs and restaurants—including the legendary ABC Kitchen's Squash Toast.”

—MindBodyGreen.com

“An exuberant take on vegetables” and one of “Our Top 10 Cookbooks for 2016”

—Newsday

“The editors of Lucky Peach, a quarterly food magazine founded by former NYT restaurant critic Peter Meehan and chef Momofuku’s David Chang, are on a mission to add a little boom boom pow to your weeknight cooking. This assortment of meat-free meals moves beyond pasta and grain bowls, putting produce front and center with help from guest contributors like Chang, Jessica Koslow of Sqirl, and Brooks Headley and Julia Goldberg of Superiority Burger.”

—InStyle

“A raucous pileup of umami-stoked veggies photographed with kitschy action figures. The recipes are easy and accessible...”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Any book with an exclamation point in its title promises to be a good time, and the third book from the Lucky Peach editors doesn’t disappoint. They switch gears after their previous meat-centric cookbook with 100-plus recipes that show vegetables are anything but boring, like tempura green beans with honey mustard and bright, charred carrots.”

—TastingTable.com

“Proof that vegetables are cool: They’re getting the Lucky Peach treatment.”

—The Washington Post

“The humorous and diverse roster of recipes from top chefs including Ivan Orkin, David Chang and Jessica Koslow is made far less intimidating by witty commentary, quick Q & A’s and detailed instructions that feel as if your very talented, very cool chef friend is teaching you some cherished industry secrets.”

—PasteMagazine.com

“The idea that vegetables can make up a full, satisfying meal is no longer a novel concept... But now cooking weekday meals with this emphasis just got a whole lot easier, thanks to a new cookbook from Lucky Peach. And as its title, Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!, suggests, there are no weak links or dribble-y leeks to be found here.”

—Vogue.com

“If any publication is going to make cooking vegetables fun, it’s Lucky Peach. Plus, chefs such as Ivan Orkin and Brooks Headley contributed recipes.”

—GrubStreet.com

“Lots of brightly colored graphics and photographs that are themselves mostly fun and a bit silly (one shows blue cheese dressing for a wedge salad also being poured over toy trucks and shoes), as well as recipes that one could say the same thing about: daikon with X.O. sauce, foil-wrapped vegetables, Kung Pao celeries, miso butterscotch.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Meehan and his fellow editors at Lucky Peach magazine have produced a book of entirely charismatic vegetable dishes. Readers will find the likes of Buffalo cucumbers, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie, Sichuan squash stew, and zucchini mujadara, along with input from hotshot chefs such as David Chang and Ivan Orkin.”

—Boston Globe

—The New York Times

One of “Fall's 6 Best Food Books”

—The Wall Street Journal

“Lucky Peach’s Power Vegetables is the Van Halen air guitar solo of plant-centric cooking... Lifelong herbivores, skeptics who cohabitate with vegetarians, and omnivores looking to diversify their repertoires will benefit from the bold fare in Power Vegetables, spanning from zucchini pizza, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie (spoiler: it’s lamb-free!), and this vibrantly photogenic borscht.”

—USA Today

“As with so much of what Lucky Peach does, the balance between irreverence and utter seriousness of purpose makes this book a delight. The playful visuals and Meehan’s off-the-cuff text offer near-constant reminders that vegetables are wildly versatile, and cooking them ought to be fun.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Peter Meehan (and the editors of Lucky Peach) found a way to make a vegetable cookbook that you'll want to read as much as you want to (lick the pages) cook from.”

—Food52.com

“Aggressively tasty vegetables”

—NYTimes.com

“The indie food magazine Lucky Peach has made our dreams come true with their new cookbook Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!: Turbocharged Recipes for Vegetables With Guts, in which the editors of the quarterly mag share all the best vegetable-focused dishes from our favorite chefs and restaurants—including the legendary ABC Kitchen's Squash Toast.”

—MindBodyGreen.com

“An exuberant take on vegetables” and one of “Our Top 10 Cookbooks for 2016”

—Newsday

“The editors of Lucky Peach, a quarterly food magazine founded by former NYT restaurant critic Peter Meehan and chef Momofuku’s David Chang, are on a mission to add a little boom boom pow to your weeknight cooking. This assortment of meat-free meals moves beyond pasta and grain bowls, putting produce front and center with help from guest contributors like Chang, Jessica Koslow of Sqirl, and Brooks Headley and Julia Goldberg of Superiority Burger.”

—InStyle

“A raucous pileup of umami-stoked veggies photographed with kitschy action figures. The recipes are easy and accessible...”

—Atlanta Journal Constitution

“Any book with an exclamation point in its title promises to be a good time, and the third book from the Lucky Peach editors doesn’t disappoint. They switch gears after their previous meat-centric cookbook with 100-plus recipes that show vegetables are anything but boring, like tempura green beans with honey mustard and bright, charred carrots.”

—TastingTable.com

“Proof that vegetables are cool: They’re getting the Lucky Peach treatment.”

—The Washington Post

“The humorous and diverse roster of recipes from top chefs including Ivan Orkin, David Chang and Jessica Koslow is made far less intimidating by witty commentary, quick Q & A’s and detailed instructions that feel as if your very talented, very cool chef friend is teaching you some cherished industry secrets.”

—PasteMagazine.com

“The idea that vegetables can make up a full, satisfying meal is no longer a novel concept... But now cooking weekday meals with this emphasis just got a whole lot easier, thanks to a new cookbook from Lucky Peach. And as its title, Lucky Peach Presents Power Vegetables!, suggests, there are no weak links or dribble-y leeks to be found here.”

—Vogue.com

“If any publication is going to make cooking vegetables fun, it’s Lucky Peach. Plus, chefs such as Ivan Orkin and Brooks Headley contributed recipes.”

—GrubStreet.com

“Lots of brightly colored graphics and photographs that are themselves mostly fun and a bit silly (one shows blue cheese dressing for a wedge salad also being poured over toy trucks and shoes), as well as recipes that one could say the same thing about: daikon with X.O. sauce, foil-wrapped vegetables, Kung Pao celeries, miso butterscotch.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Meehan and his fellow editors at Lucky Peach magazine have produced a book of entirely charismatic vegetable dishes. Readers will find the likes of Buffalo cucumbers, Tex-Mex shepherd’s pie, Sichuan squash stew, and zucchini mujadara, along with input from hotshot chefs such as David Chang and Ivan Orkin.”

—Boston Globe

Author

Excerpt

INTRODUCTION

I like a lot of vegetable cookbooks, so when we decided to make one ourselves, it meant I had to think about how to approach vegetable cookery from a Lucky Peach perspective.

I didn’t want to tell you to cook with what’s in season (you have already been told to do this) or to treat your beautiful in-season vegetables simply (ditto). I didn’t want to put together a vegetable/vegetarian cookbook for its explicit healthfulness or wholesomeness, though I appreciate and welcome those qualities in any dish, vegetable or not.

I wanted the book to be 98% fun and 2% stupid. I wanted something that took the sweaty, anxious what-are-we-going-to-eat-this-week feeling that sometimes casts a shadow over a Sunday trip to the supermarket and answered it, yelling WE ARE GOING TO EAT VEGETABLES AND THEY ARE GOING TO BE AWESOME.

Look, when I come home from work to a bowl of rice and some steamed broccoli and maybe a little jarred Chinese chili crisp, I’m a happy camper. But sometimes you need more: You need vegetables that are going to be exciting, that will push easy meat- or carb-centric dishes out of the spotlight. Which means they need to be what?

Powerful.

So I knew what we needed. And by that point in the book-making process not only did I want an exclamation point at the end of the title, I was thinking in all caps. Thinking meaningless success-o-slogans like FLAVOR IS POWER and EASE IS POWER and SIZE IS POWER and FIRE IS POWER and POWER IS POWER. I wanted weeknight all-caps cooking for people looking to eat more vegetable-centered meals.

What is all-caps cooking? It means center-of-the-meal dishes or certainly center-of-attention cooking. Elote—a Mexican way of gussying up corn on the cob (see page 156)—is a perfect example of a side dish or an appetizer in the Power Vegetables! style. Regardless of what you’ve got on the menu at your grill-out, you’re not going to have leftover elote, and if I’m there I’m probably gonna fill up on them and neglect the burgers.

It means vegetable dishes with real flavor. Flavorfulness is subjective, and it alone does not translate into power. There were any number of dishes that we tasted in the making of the book that we’d eat and enjoy and then sit there looking at, asking the question: But are you powerful, little plate of vegetables? And in that moment, there were many delicious things that were then either cast aside or amped up. For me, pappa al pomodoro was too plain, but pappa al pomodoro crossed with English muffin toaster pizzas (see page 136) gave my cerebellum the right amount of tingle. Traditional vichyssoise barely squeaked by—it’s almost too simple—but a variation on vichyssoise made with dashi (see page 138) is clearly a PV.

The idea of what constituted a power vegetable mutated over time. The original over-the-top subtitle I had in mind for this book was: “102 turbo-charged recipes that will push the meat off your plate—except for the meat that’s in them!”

See, I originally conceived of meaty vegetable dishes standing shoulder-to-shoulder with naturally vegetarian or vegan ones. But as we started to test and sort and select, I thought about what I really wanted to be eating. (I would say “what people who buy this book want to be eating,” but I can’t really judge your situation/needs/wants, since you are, at this moment, a fictional, collective construct propelling this introduction.) And that is why what I thought constituted a power vegetable when we set this ship out to sail is different from what I do here on the shore we’ve landed on. How so?

The biggest and most important change is that meat is gone—terrestrial flesh, at least. (There is passing mention of optional bacon in a couple of places; because it is bacon, I felt like that was okay.) But you’ll have to pry anchovies and their umami-rich brethren from my cold, dead hands.

There were dishes where this mattered more than I thought it would, like mapo tofu, which really gets a lot of power from the little bit of meat that is usually in it, which meant it was just more work than we anticipated to get our mushroom-based version (see page 132) up to par. There were dishes where I thought I’d miss it, like the French Onion Soup (page 126), and it turns out it was the vegetables making the dish delicious all along, like that story about Jesus and one set of footprints on a beach, and the onions are Jesus.

I thought that after we published 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I’d let myself relapse into the old Lucky Peach way of running impenetrable-but-interesting cheffy recipes, at least for some portion of the book. We’d examine Jeremy Fox’s influential Green Peas in White Chocolate or investigate how to put together a gargouillou à la Michel Bras or maybe dig out Roxanne Klein and Charlie Trotter’s catalog of high-end raw food cooking. But it came down to the same question: Is that really what we’re going to eat at home, what we’re going to cook? Is that where the POWER in VEGETABLES is?

I’ll go yes and no on that. If you have the means, the time, and the talent, there’s a lot to be said for advanced vegetable manipulation: how textures can be twisted, how flavors can be layered, how the composition of a dish can affect how it eats. But at home, how often are you or how often am I going to make that kind of food? I want you to be cooking from this book, preferably all the time. We have borrowed many of the recipes here from chef friends/acquaintances/ crushes, but we’ve focused on their most doable work, not their most refined.

Instead you will notice there are four spots in the book where we stop with the relentless recipeness of it all and talk to some chefs about what a power vegetable is to them. David Chang, Brooks Headley, Julia Goldberg, Jessica Koslow, and Ivan Orkin all weigh in.

Chef-sourced or otherwise, we’ve tried to make and keep the recipes easy. EASE IS POWER, after all, because what is more powerful than being able to turn ingredients into a desirable dinner with minimal effort? Almost nothing.

And with 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I learned that readers like knowing the rules of engagement up front. In that book, we did no frying, for example, and banished subrecipes. In these pages, we’ve allowed ourselves to wade into the hot oil a little more often, and subrecipes have been let in as long as they behave themselves and don’t have you jumping all over the book. The specific limitations we put on ourselves for this collection include:

1. NO PASTA RECIPES

I love pasta sooooooooo much. Too much? Maybe. What I’ve found over the years is that at home we’ll turn vegetables into a pasta sauce as a de facto option. I wanted this to be a slate of recipes that would give me new ideas for dinner and keep me from carbo-loading when I’m not eating meat. That said, nearly everything in here, or some form of its leftovers, would be eatable over pasta.

2. NO EGG-ON-IT DISHES; NO GRAIN BOWLS

There is nothing more in vogue at the time that this book is going to press than a bowl of some kind of grain—rice or quinoa or what have you—topped with some vegetables and pickles, crowned with a runny egg. And while we probably could’ve filled twenty pages of this book with thoughts on them, they’re kind of in the same class as pasta: You can put nearly any dish (or leftovers of any dish) from this book on a bowl of grains, nestle some appealing pickles in there and opt in to a runny egg if you like, and you will be stoked and well fed. But I’m not sure you need us to tell you much more about it.

3. FISH AND DAIRY ARE OKAY WITH US

After kicking meat out of the book, I was confronted with a choice: Should this be a 100% vegetarian or vegan book? For Power Vegetables!, I felt that the answer had to be no. Most of the vegetarians in my life eat fish. (I know that technically makes them “pescatarians,” but the number of people who self-identify with that term has to be statistically tiny.) Most eat dairy. And this isn’t a book exclusively for those who shun meat—if anything, I’m approaching it as an omnivore who wants things to be delicious first and foremost. But as with climate change, there’s no denying that the modern diet leans too heavily on meat and wheat, so it’s good to mix things up.

4. FRUITS ARE VEGETABLES

What, did you want the book to be all potatoes? As any six-year-old can tell you, cucumbers and tomatoes and squash and things with seeds in them are not vegetables. We are saying this to the six-year-old, “Pipe down, honey, we’re trying to get dinner on the table.”

Okay. That’s it. This is and these are POWER VEGETABLES!

pfm

I like a lot of vegetable cookbooks, so when we decided to make one ourselves, it meant I had to think about how to approach vegetable cookery from a Lucky Peach perspective.

I didn’t want to tell you to cook with what’s in season (you have already been told to do this) or to treat your beautiful in-season vegetables simply (ditto). I didn’t want to put together a vegetable/vegetarian cookbook for its explicit healthfulness or wholesomeness, though I appreciate and welcome those qualities in any dish, vegetable or not.

I wanted the book to be 98% fun and 2% stupid. I wanted something that took the sweaty, anxious what-are-we-going-to-eat-this-week feeling that sometimes casts a shadow over a Sunday trip to the supermarket and answered it, yelling WE ARE GOING TO EAT VEGETABLES AND THEY ARE GOING TO BE AWESOME.

Look, when I come home from work to a bowl of rice and some steamed broccoli and maybe a little jarred Chinese chili crisp, I’m a happy camper. But sometimes you need more: You need vegetables that are going to be exciting, that will push easy meat- or carb-centric dishes out of the spotlight. Which means they need to be what?

Powerful.

So I knew what we needed. And by that point in the book-making process not only did I want an exclamation point at the end of the title, I was thinking in all caps. Thinking meaningless success-o-slogans like FLAVOR IS POWER and EASE IS POWER and SIZE IS POWER and FIRE IS POWER and POWER IS POWER. I wanted weeknight all-caps cooking for people looking to eat more vegetable-centered meals.

What is all-caps cooking? It means center-of-the-meal dishes or certainly center-of-attention cooking. Elote—a Mexican way of gussying up corn on the cob (see page 156)—is a perfect example of a side dish or an appetizer in the Power Vegetables! style. Regardless of what you’ve got on the menu at your grill-out, you’re not going to have leftover elote, and if I’m there I’m probably gonna fill up on them and neglect the burgers.

It means vegetable dishes with real flavor. Flavorfulness is subjective, and it alone does not translate into power. There were any number of dishes that we tasted in the making of the book that we’d eat and enjoy and then sit there looking at, asking the question: But are you powerful, little plate of vegetables? And in that moment, there were many delicious things that were then either cast aside or amped up. For me, pappa al pomodoro was too plain, but pappa al pomodoro crossed with English muffin toaster pizzas (see page 136) gave my cerebellum the right amount of tingle. Traditional vichyssoise barely squeaked by—it’s almost too simple—but a variation on vichyssoise made with dashi (see page 138) is clearly a PV.

The idea of what constituted a power vegetable mutated over time. The original over-the-top subtitle I had in mind for this book was: “102 turbo-charged recipes that will push the meat off your plate—except for the meat that’s in them!”

See, I originally conceived of meaty vegetable dishes standing shoulder-to-shoulder with naturally vegetarian or vegan ones. But as we started to test and sort and select, I thought about what I really wanted to be eating. (I would say “what people who buy this book want to be eating,” but I can’t really judge your situation/needs/wants, since you are, at this moment, a fictional, collective construct propelling this introduction.) And that is why what I thought constituted a power vegetable when we set this ship out to sail is different from what I do here on the shore we’ve landed on. How so?

The biggest and most important change is that meat is gone—terrestrial flesh, at least. (There is passing mention of optional bacon in a couple of places; because it is bacon, I felt like that was okay.) But you’ll have to pry anchovies and their umami-rich brethren from my cold, dead hands.

There were dishes where this mattered more than I thought it would, like mapo tofu, which really gets a lot of power from the little bit of meat that is usually in it, which meant it was just more work than we anticipated to get our mushroom-based version (see page 132) up to par. There were dishes where I thought I’d miss it, like the French Onion Soup (page 126), and it turns out it was the vegetables making the dish delicious all along, like that story about Jesus and one set of footprints on a beach, and the onions are Jesus.

I thought that after we published 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I’d let myself relapse into the old Lucky Peach way of running impenetrable-but-interesting cheffy recipes, at least for some portion of the book. We’d examine Jeremy Fox’s influential Green Peas in White Chocolate or investigate how to put together a gargouillou à la Michel Bras or maybe dig out Roxanne Klein and Charlie Trotter’s catalog of high-end raw food cooking. But it came down to the same question: Is that really what we’re going to eat at home, what we’re going to cook? Is that where the POWER in VEGETABLES is?

I’ll go yes and no on that. If you have the means, the time, and the talent, there’s a lot to be said for advanced vegetable manipulation: how textures can be twisted, how flavors can be layered, how the composition of a dish can affect how it eats. But at home, how often are you or how often am I going to make that kind of food? I want you to be cooking from this book, preferably all the time. We have borrowed many of the recipes here from chef friends/acquaintances/ crushes, but we’ve focused on their most doable work, not their most refined.

Instead you will notice there are four spots in the book where we stop with the relentless recipeness of it all and talk to some chefs about what a power vegetable is to them. David Chang, Brooks Headley, Julia Goldberg, Jessica Koslow, and Ivan Orkin all weigh in.

Chef-sourced or otherwise, we’ve tried to make and keep the recipes easy. EASE IS POWER, after all, because what is more powerful than being able to turn ingredients into a desirable dinner with minimal effort? Almost nothing.

And with 101 Easy Asian Recipes, I learned that readers like knowing the rules of engagement up front. In that book, we did no frying, for example, and banished subrecipes. In these pages, we’ve allowed ourselves to wade into the hot oil a little more often, and subrecipes have been let in as long as they behave themselves and don’t have you jumping all over the book. The specific limitations we put on ourselves for this collection include:

1. NO PASTA RECIPES

I love pasta sooooooooo much. Too much? Maybe. What I’ve found over the years is that at home we’ll turn vegetables into a pasta sauce as a de facto option. I wanted this to be a slate of recipes that would give me new ideas for dinner and keep me from carbo-loading when I’m not eating meat. That said, nearly everything in here, or some form of its leftovers, would be eatable over pasta.

2. NO EGG-ON-IT DISHES; NO GRAIN BOWLS

There is nothing more in vogue at the time that this book is going to press than a bowl of some kind of grain—rice or quinoa or what have you—topped with some vegetables and pickles, crowned with a runny egg. And while we probably could’ve filled twenty pages of this book with thoughts on them, they’re kind of in the same class as pasta: You can put nearly any dish (or leftovers of any dish) from this book on a bowl of grains, nestle some appealing pickles in there and opt in to a runny egg if you like, and you will be stoked and well fed. But I’m not sure you need us to tell you much more about it.

3. FISH AND DAIRY ARE OKAY WITH US

After kicking meat out of the book, I was confronted with a choice: Should this be a 100% vegetarian or vegan book? For Power Vegetables!, I felt that the answer had to be no. Most of the vegetarians in my life eat fish. (I know that technically makes them “pescatarians,” but the number of people who self-identify with that term has to be statistically tiny.) Most eat dairy. And this isn’t a book exclusively for those who shun meat—if anything, I’m approaching it as an omnivore who wants things to be delicious first and foremost. But as with climate change, there’s no denying that the modern diet leans too heavily on meat and wheat, so it’s good to mix things up.

4. FRUITS ARE VEGETABLES

What, did you want the book to be all potatoes? As any six-year-old can tell you, cucumbers and tomatoes and squash and things with seeds in them are not vegetables. We are saying this to the six-year-old, “Pipe down, honey, we’re trying to get dinner on the table.”

Okay. That’s it. This is and these are POWER VEGETABLES!

pfm

Copyright © 2016 by Peter Meehan and the editors of Lucky Peach. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Back to Top

Notifications