A Brief History of the Caesar1969. It’s a year for wild innovations, unexpected upheavals, and bold leaps forward. Hair is getting longer, music louder, cars faster. Led Zeppelin release their first album.

Easy Rider roars into the theatres.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus debuts on TV. Four computers from different universities “talk” to one another for the first time, through the ARPANET. People take to the streets to protest the war in Vietnam. The Zodiac Killer stalks northern California, while Charles Manson and his “family” gather in the south. Roughly 400,000 people travel to a dairy farm near Woodstock, NY, for a music festival.

Here in Canada, Trudeaumania (father, not son) is in full swing. The Front de libération du Québec bomb the Montréal Stock Exchange. The Montréal Expos play their inaugural home game at Jarry Park, securing a rare victory on their way to tying for the worst record in the league. A few blocks away from the stadium, John Lennon and Yoko Ono spend a week in bed in Room 1742 of the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, where they record “Give Peace a Chance.”

And everyone everywhere watches Neil Armstrong take a walk on the moon.

In the middle of all this change, Walter Chell stands behind the counter of the Owl’s Nest, the fine-dining lounge of the Calgary Inn, a downtown hotel a short walk from the recently completed Husky Tower. Tonight, as always, Walter’s wearing his steel-rimmed glasses, an expertly tailored blazer, a white Oxford shirt, an understated black tie, and a fine Swiss watch. With his dark pomaded hair and carefully groomed moustache, he’s more Jazz Age than Summer of Love. And unbeknownst to him, he’s about to secure a spot in the history books for himself.

The owners of the Calgary Inn had asked Walter, their food and beverage manager, to create a signature drink to celebrate the opening of Marco’s, the hotel’s new Italian restaurant. The request got him thinking about his favourite meal from his years living in Italy, spaghetti alle vongole, and wondering if he could recreate its flavours in a cocktail. He cooked clams and strained tomatoes, adding and subtracting ingredients until he found the perfect combination.

Behind the bar in the dimly lit Owl’s Nest, Walter gets ready to serve his new cocktail. We can’t know for sure what’s playing on the lounge stereo, but it being 1969 in Canada, there’s a good chance it’s Winnipeg’s own The Guess Who, whose “These Eyes” has recently become their first top-ten hit. The regulars could be making their cases for best player in the then 12-team NHL: Esposito or Gordie? Which Bobby: Hull or Orr? Serge Savard, whose Habs have just won their second Stanley Cup in a row? Or, like many others across the country, maybe they’re complaining about the CBC cancelling the folk musical variety show

Don Messer’s Jubilee, which often rivalled

Hockey Night in Canada as the most popular show in the nation during its 12-year run. Walter, however, prefers listening to talking, even though, hailing from Montenegro by way of Italy and Switzerland, he speaks seven languages.

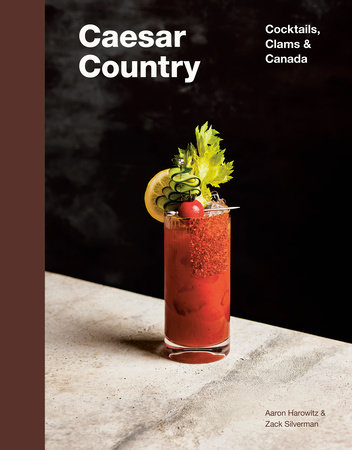

Quietly, then, he pours some celery salt on a plate, rubs the rim of a highball glass with some lime, and rolls the rim into the salt before placing a couple of ice cubes in the glass. In a cocktail shaker he combines his house-made mix of clam juice and tomato juice with ashot of vodka, four dashes of Worcestershire sauce, pepper, and what he later says was his “secret ingredient”: a dash of oregano. He fills the shaker with ice, stirs the mix gently with a bar spoon, and strains the drink into the glass. He garnishes the cocktail with a wedge of fresh lime and a celery stick, and serves it for the first time. Price: $1.80.

Walter himself is not actually a fan of his cocktail. It’s just “not his cup tea,” as he’ll later tell reporters. He prefers scotch on the rocks, with a splash of water. But he knows a hit when he tastes it. And he knows that a great drink needs a great name. With a nod to the homeland of spaghetti alle vongole, he calls it the Caesar.

So begins a local craze. You can imagine it travelling, almost block by block, as the bartenders of Calgary start adding it to their arsenal, and then to Edmonton, Banff, and across the country. Home bartenders start serving it at parties, helped by the arrival in Canada that same year of Mott’s Clamato Cocktail, a canned blend of clam and tomato juices made by Duffy-Mott, an American company specializing in juices and sauces.

At least, this is the version of the Caesar’s origin story that we find most convincing, based on our research. Cocktail origin stories are, by their nature, often a bit murky. As bartender and historian Jim Meehan points out, “Given the sensitive and private nature of the guest/ bartender relationship, the history of what happens in bars is largely an oral tradition, transmitted through the hazy fog of a night of drinking . . . Depending on whom you ask, even recent innovations are shrouded in mystery.”

Certainly, there were earlier iterations of clam-based cocktails, and there are records of cocktails featuring some combination of clams, tomatoes, spices, and vodka being served at various moments in the first half of the 20th century in bars in Paris and New York. We don’t know if Walter Chell ever sampled such a drink on his travels or if he was aware that such a combination had been tried before. He would have been familiar with the Bloody Mary, to be sure.

What we do know beyond doubt is that Walter Chell popularized the clam, tomato, and vodka cocktail, coming up with its ideal portions, spicing, flavour additions, and garnish. And that he gave it the name that helped it to become iconic, while doing more than any other person to popularize it. Walter Chell and the origin of the Caesar are inextricably linked.

Copyright © 2022 by Aaron Harowitz and Zack Silverman. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.