***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected copy proof*** Copyright © 2018 Nicholas Smith

“It’s gotta be the shoes.” Most people have heard it, even if they can’t remember the source: a 1989 commercial for the Nike Air Jordan IIIs. In the commercial, Spike Lee, playing his alter ego Mars Blackmon from the movie She’s Gotta Have It, lists all the possible reasons Michael Jordan is “the best player in the universe.”

His dunks? asks Lee.

No, Mars, says Jordan.

His shorts? asks Lee.

No, Mars, says Jordan.

His bald head? asks Lee.

No, Mars, says Jordan.

His shoes? asks Lee.

Jordan denies it, but Lee keeps circling back to the shoe guess. In the thirty-second ad, the word “shoes” is spoken ten times.

Before the familiar swoosh appears onscreen, a cheeky disclaimer informs us that “Mr. Jordan’s opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Nike, Inc.,” but everyone already knows the message here: “It’s gotta be the shoes.”

Nike sold millions of Air Jordans through that ad campaign, and Lee’s most famous line was bound for pop culture immortality. But the ad didn’t work just because it was catchy and star- studded; it was also a clever update of an idea that most of us have lived with from a young age: the idea of magical shoes.

Cinderella’s glass slipper makes her a princess. Dorothy’s ruby slippers not only transport her back to Kansas but keep the Wicked Witch of the West at bay. Puss-in-Boots’ request for foot- wear helps him win legitimacy for his master. With his winged sandals Hermes can fly. The “seven-league boots” of European folklore let the wearer travel great distances in a single step. A young orphan’s shoes compel her to dance in Hans Chris- tian Andersen’s “The Red Shoes” and in the Grimms’ version of “Snow White,” the wicked stepmother dances herself to death in charmed red-hot iron heels.

Fast-forwarding a few centuries, Lil’ Bow Wow finds a pair of magic sneakers that let him play professional basketball in 2002’s Like Mike, and in the Harry Potter series a teleporting “portkey” comes in the form of an old boot. And at the end of the first Sex and the City movie, the first thing Carrie Bradshaw uses in her new apartment-sized closet—a fairy tale for anyone familiar with Manhattan real estate—is the shoe rack.

When Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were collecting their folk- tales in the early eighteenth century, footwear sometimes did mean the difference between life and death, as well as between rungs of the social ladder. Without owning a reliable pair of boots, finding work was difficult; sturdy shoes gave the lower-class wearer the unmagical but useful ability not to starve to death. Until the mid-1800s, shoes were made entirely by hand in a long and costly process. The supply was always limited, and shoes were coveted highly enough to inspire generations of storytellers.

Shoes may no longer mean the difference between starving and not, but they still have great symbolic power. It’s embedded in our language: to understand each other we must “walk a mile” in someone’s shoes. A guess about one’s character will prove true “if the shoe fits.” Someone irreplaceable has “hard shoes to fill.” Someone may offer to “eat his shoe” if he’s wrong. An uncomfortable reversal means that “the shoe is on the other foot.” Before the inevitable, we wait for “the other shoe to drop.”

As objects, our contact with shoes is unusually intimate: shoes change, adjust, and warp to fit us like no other piece of clothing. Finding a worn-out vintage rock tee at a Goodwill store might be a hipster’s treasure; finding a worn-out pair of sneakers is infinitely less so. Their soles both connect us to our environment and protect us from it. They can be either utilitarian or expressive or both, whatever we choose. Somewhere in these qualities is, maybe, the source of their appeal as, well, more than shoes.

Which takes us back to Jordan and his Nikes. Ever since there have been sports stars to look up to, kids have played their heroes on the fields, courts, and sandlots. “I’m DiMaggio. I’m Elway. I’m LeBron.” By pairing the superhuman Jordan with the Everyman Lee, the Nike commercials suggested that there was a way to bridge the gap—a hundred-dollar way, but a way nonetheless. It was a modern version of the old story: an ordinary kid could wear a pair of sneakers and jump like the Jumpman, just as a farm girl could put on a pair of red slippers to get home from the Land of Oz.

For a long time, sneakers weren’t something I thought about. Growing up, they were just shoes you wore every day until they wore out. The first sneakers I can remember treating with any reverence were a pair of Nike Air Flight Turbulence I wore when I played basketball freshman year of high school. I bought them partly because they’d been advertised in a campaign featuring Damon Stoudamire, a rookie point guard for the Toronto Raptors whom I knew from his time with the Arizona Wildcats, the most popular college team in my hometown. I also bought them be- cause they were last year’s model and retailed for $40 at the Nike outlet, a steal at a time when the latest Air Jordan sold for $150.

I loved them, with their wavy black-and-white lines and familiar swoosh. For the duration of my freshman season I wore them only for practice and games, after which they went right back into the box. They might not have helped a lanky, uncoordinated fourteen-year-old score a career high of five points, but I sure felt like they did. The one time I wore them off court was when friends who had moved away from my small town came to visit. They had new haircuts, new glasses, a binder full of new CDs. I had my new shoes.

It would be years before I again found that sneaker magic. Basketball had long since melted away and been replaced by distance running when I read Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run, an ode to distance running that featured unforgiving 100-mile races, a colorful cast of “ultrarunners,” punishing desert environments, and an indigenous Mexican tribe whose members seem to run forever in thin sandals. As a marathoner with recurring knee pain, I was interested in what McDougall had found to be a near constant among ultrarunners: minimalist footwear. The implicit promise of the book seemed to be that I could join their tribe and kiss knee pain good-bye by ditching my chunky Nikes. It had to be the shoes.

I zeroed in on the then-popular Vibram FiveFingers, which looked as ridiculous as their name—like gorilla feet, with a separate compartment for each toe. But I was suddenly a true believer; I wasn’t looking for sneakers anymore, I was looking for a spiritual conduit to the natural world, a connection with some evolutionary past of perfect endurance and form. Shoes shaped like feet seemed about right. I walked into a specialty running store and told the clerk what I was looking for, how the FiveFingers would instantly cure me of pain and allow me to run forever.

The clerk broke the spell. He cautioned that plunging down from a big, chunky Nike down to a barely there slip-on was a recipe for creating joint pain, not ending it. I instead ended up walking out of the store with a pair of electric blue Brooks Pure-Connect, an ultralight shoe that still had some cushioning—and, unlike the FiveFingers, still resembled a sneaker.

My new shoes made me feel different. Not just because of the way the Brooks sneakers were built (they gripped my midfoot in a way my previous Nikes hadn’t) but also because they broke with my pattern of black, gray, or white shoes. For whatever reason, I realized, the all-blue shoes made me feel like a faster runner. Whether that was actually the case was beside the point.

No shoe is more variable than the sneaker. Whether you know them as sneakers, trainers, gym shoes, tennis shoes, joggers, or runners, almost everyone has owned a pair. Sneakers can help us stand out or blend in. They can be the item we build our outfits up from or an afterthought we slip on before running out the door. And every sneaker we wear says something about us in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

I saw a glimpse of the many permutations of sneakers at the 2014 Boston Marathon. I had yet again missed out on qualifying for the race, but, being a marathon fan, I closely followed the broadcast on TV and online. One year after the terrorist bombing that had taken the lives of three people and injured hundreds of others, sneakers were the centerpiece of makeshift memorials at Copley Square near the site of the attack, draped over crowd barriers or carefully placed alongside more conventional offerings of flowers and handwritten notes. An exhibit in the nearby Boston Public Library artfully arranged running shoes collected from the previous year’s memorial. Outside, high-tech racing flats were on the feet of tens of thousands of participants. Spectators lining the route wore a rainbow of basketball and tennis shoes. Sophisticated engineering and innovative soles allowed amputee athletes to compete. Along the 26.2-mile course, old shoes hung from telephone wires overhead.

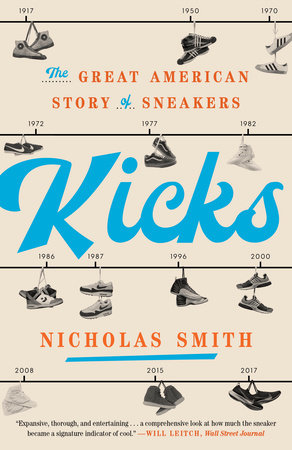

Athletic equipment, limb replacement, all-purpose fashion, memorial, artwork: in a century and a half of existence, sneakers have become one of our most quietly ubiquitous cultural objects. Sneakers were born at the meeting of the Industrial Revolution and its unlikely by-product, increased leisure time. They grew as sports began to organize. They helped US soldiers train for World War II. They evolved with fashion and consumer culture. They defined the image of both the suburban teenager and gang culture. They appeared in song lyrics at the birth of hip-hop and the were part of the uniform of young punks and aging rock stars alike. They helped create the celebrity athlete and became a universal symbol of globalization. Presidents have worn them, and so has everyone else. The history of sneakers is, in a sense, the recent history of the United States.

So how did we get here?

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.