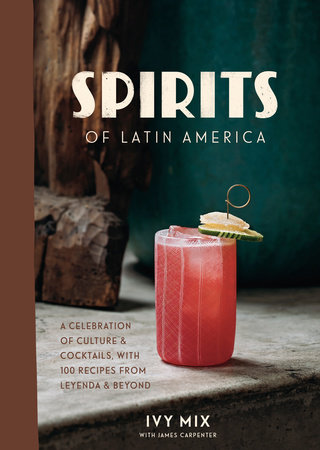

Introduction “It’s a simple law of physics: energy doesn’t die or go away, it has to be transmitted. It is through talking, dancing, and laughing that it is released. Latin spirits are the base for our celebration.”—Carlos Camerena, La Alteña Distillery

I grew up in a very small town in central Vermont. By small, I mean

really small—seven-hundred-people small—the type of town where everyone not only knows your name but they know everything about you, too. It was also far from cities or airports, so growing up, my experience of the big wide world was pretty limited.

When I decided to attend a liberal-arts college (again in Vermont), my life changed. The school year there was broken up into trimesters, and during the winter trimester each year, we were required to leave campus and complete study work in our field. I had zero idea what I wanted to do with myself or what my “field” would be—I just knew I wanted to go somewhere—

anywhere—outside the country, learn a foreign language, and see something different from what I was used to. Though I didn’t recognize it quite yet, I was suffering from a classic case of wanderlust.

I ended up in Antigua, Guatemala. A couple of days after I arrived, I stumbled into Antigua’s now-famous Café No Sé, sat down, ordered a cerveza, and did my best to pretend that my nineteen-year-old self belonged in a bar. I enjoyed the place so much, I went back the next night—and every night thereafter for the whole two months I was in Antigua. When I returned to Vermont, I couldn’t wait to turn around and go back again—which led to Guatemala being my home, and bartending my job, for about half of each year while I finished my degree. Whenever I was there, I spent my nights working and my days exploring, immersing myself in this foreign land that felt like home. Antigua is a particularly quaint little colonial town, and I would spend hours every day roaming the cobblestone streets and visiting the markets before I went to work.

Far from being cured by this experience, my wanderlust continued to grow. My travels began to take me to other parts of Latin America: first to Mexico with John, the owner of Café No Sé, to smuggle mezcal from Oaxaca back to Guatemala; then to Peru, followed by a stint in Argentina and beyond. Afterward, I moved to New York and began bartending there, finding ways and reasons to travel south whenever I could.

In 2015, I opened my bar, Leyenda, in Brooklyn—a bar dedicated to celebrating the Latin American cultures I’d fallen in love with. I’d been living in New York for seven years and was missing Latin America so much that I knew I was either going to have to move back down there or bring a little of there back to me. Leyenda was my solution—one way for me to bring my passion for bartending and my passion for Latin America together.

This book is another solution. Traveling south and getting to know Latin American people and their cultures, in part through what they drink, has taught me to relate to other people as a member of a global social society, rather than the island of one that I’d always felt before. With this book, I want to offer another context in which to do just that—to see ourselves as joined together with other cultures via their traditional spirits.

Many of the classic cocktails we know best come from Latin America—from the daiquiri to the margarita, the pisco sour to the Mojito. But in comparison with much of the rest of the world, Latin America doesn’t have much of a cocktail culture to speak of. What it does have is a rich and vital tradition of spirits distillation.

As a bartender who loves experimenting with flavor, I count the spirits of Latin America among my greatest inspirations; the cultural richness of these places is paralleled by the full, distinctive flavor of the spirits themselves. Spirits are like a palette of colors—you don’t want one blue and one yellow to paint with; you want all of the shades within them. I want

big flavors to create my drinks from; and to me, no other group of spirits has more life and vivaciousness and Technicolor flavor than that from Latin America. From the bright floral tints of Peruvian pisco to the earthy smokiness of Oaxacan mezcal, these are flavors that give me a

lot to work with and can be made into some of the brightest, most vivid cocktails out there.

There’s a word in wine culture that you’ve probably heard before: terroir. There is no direct English translation for this term, but it basically refers to the way geographic factors such as land, soil, topography, and climate impart flavors and other sensations to wine. I argue that terroir applies to all sorts of food and drink—and that it isn’t just the land that affects the product, but also the identities, history, and culture of the places where foods and beverages come from. There are concrete reasons, both ecological and cultural, why Pinot Grigio ends up tasting different from, say, Verdejo, or why Chardonnay made in California tastes different from Chardonnay made in France. And there are also reasons why I don’t taste a tequila and think to myself,

Oh! Paris! There’s a connection between what I taste and the identity, the historical and cultural significance, of the people who make it: an intrinsic relationship that I think of as

cultural terroir. I wanted to understand more than just the soil composition elevation of the agave fields from which my tequila came. More significant to me than the question of

what something is made of, I realized, is the question of

why it is made at all. Why do these spirits exist? How did they come to be? What history are they a part of, and why do we drink them today? These are the questions I tried to begin answering in this book.

From a crassly commercial point of view, spirits from Latin America are certainly “having a moment” here in the United States. If you look around, just about every celebrity these days seems to have a tequila brand. A decade or so ago, the rise in popularity of tequila in particular sparked a worldwide fascination with tequila’s smokier cousin, mezcal (more on that in chapter one), and from there the list goes on and on. There’s also a significant amount of interest in all things

artisanal today. We want to get back to the essence of the thing, an essence that, in the world of food and beverage, lies in its human importance to the people who make it. Unlike, say, a lot of American bourbons, English gins, or Russian vodkas, many of the spirits of Latin America were, up until very recently, made on a small, preindustrialized scale. While this is changing—in some places dangerously quickly—many of the Latin spirits I love most are still made in a truly artisanal way.

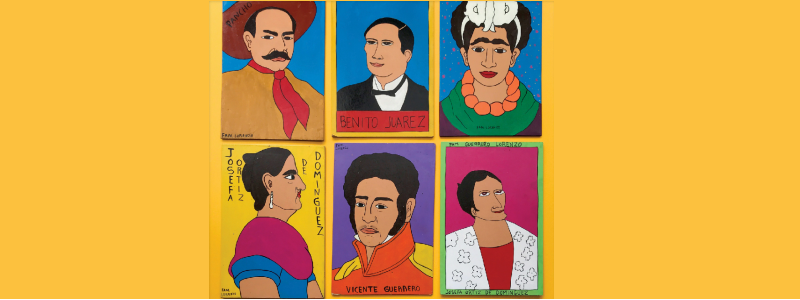

My notion of cultural terroir finds a good parallel in the idea of

patria. A concept also without a real equivalent in English—its translation from Spanish is something like “homeland,” but it means so much more—

patria is the embodiment not only of actual place but of that place’s ethos and identity. It sums up one’s national history, traditions, attitudes, and conception of belonging; it’s what we feel pride and selfless devotion for when we are patriotic; and like patriotism, it has just as much to do with the intangible constructs of national selfhood as it does with physical borders.

Copyright © 2020 by Ivy Mix. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.