Introduction

All of my earliest memories of cooking are over open fire. My mother died when I was very young and my dad and I moved around a lot from country town to country town in upstate New York. My dad worked construction and was a real outdoorsman, so there wasn’t a lot of cooking going on in the house. He would hunt venison after work during the week, and we’d cut it up in the backyard, cook it on the grill, and that was dinner. Maybe we’d boil some corn with it. We also ate at a lot of roadside grills, those public grilling areas off the side of the road in the mountains. In the winter, we’d go ice fishing and people would have grills on the ice. So there wasn’t a lot of salad making, but it created an association in me of food with fire, nature, and family—something that brings people together.

My father passed away when I was twelve, and I was sent to boarding school in the Catskills. They had a kitchen with a large grill on the side of a mountain next to a lake. That was where I spent most of my time. It was almost like a trade school, teaching the basics of how to cook, with most of our meals made over open fire. Eventually I was in charge of the meals for about seventy-five kids for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I started seeing cooking as something I could focus on to make a living. My guidance counselor recommended that I go to culinary school, and the most esteemed one in the country—the Culinary Institute of America (CIA)—was only ninety minutes away in New York.

I studied at CIA, but I left after the first year and a half because I couldn’t afford it anymore, and I was bursting at the seams to be part of a real professional kitchen. My first job was as a pastry chef at Payard in New York City. I worked for free—it felt like a better way to get an education and had better potential for making connections than being at school—and when I finished my 1:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. shift, I’d work at a deli from noon to 7:00 p.m. to make money.

My next job was working at 71 Clinton Fresh Food Group with Wylie Dufresne, who was a big proponent of molecular gastronomy. But in my mind, I wanted to get back to cooking over fire, which I was able to do for several years at Peasant with Frankie DeCarlo and Dulci DeCarlo. That’s where I really started to understand the different ways that cooking over wood fire could elevate food, as well as the joy it brought the cooks and the diners. Peasant was the best education I could possibly have had, but after six years there, I really wanted to make American farm-to-table food (Peasant was Italian, specifically Puglia). I went to work at Vinegar Hill House in Brooklyn and was working there when my soon-to-be-wife, Mya, and I took a vacation to Tulum, Mexico.

As a restaurant worker, I was always working and always broke, so I’d never really taken a vacation, let alone to Mexico. I knew nothing about Tulum, but it felt raw and exciting. Mya is very brave, and we wanted an adventure, so we returned a few times more, talking each visit about the possibility of living and working there. I knew I wanted to cook over open fire and to do something sensitive to the place and its people and resources. I had tons of restaurant experience by the time we decided to pull the trigger on opening Hartwood in a remote corner of Tulum, but nothing could prepare me for this last decade of living and cooking in the Yucatán jungle.

Outside of Argentina or Uruguay, there’s no better country than Mexico in which to get an education in open-fire cooking. There are so many ingenious grill designs that are fascinating and inexpensive and get the job done beautifully. Almost any large neighborhood market will have simple standing

anafres, steel braziers with ash pans underneath, over which you place a

comal (griddle) or grill grates. These are common in backyards and among street vendors. For larger capacity,

tambos—steel drum barrels—are commonly sawed in half to make two large receptacles for wood fire. I’ve seen steel-mesh chairs and even shopping carts set over in-ground fire pits. If you think that great grilling involves a lot of store-bought equipment and a capacious backyard, your mind will quickly change when you see a group of people making carne asada on the wheel cap of a car tire over a fire built on the side of the road.

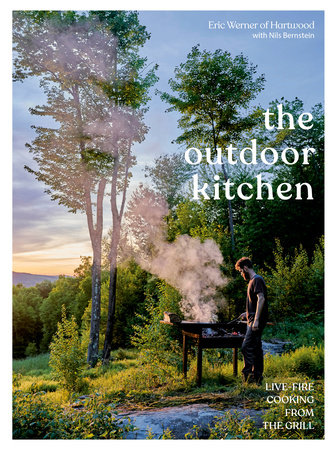

Mya and I moved to Tulum in 2010 and opened Hartwood, a restaurant located at the edge of town, between the ocean and the jungle. We now split our time between there and our family home in the Catskills. When we’re in Tulum, I’m always at the restaurant, so I really look forward to my free time in the Catskills, where I can relax at the grill with Mya and our daughter, Charlie. My love for the mountains has never left me. I love the change of seasons, and how the ingredients—and the feeling of cooking outside—are so different from month to month. Grilling isn’t something I do only when it’s sunny out; if anything, I prefer being around a hot grill when it’s cold. The smell and taste of wood-grilled food has a coziness that’s perfectly suited to fall and winter, though I love working with the vegetables, fruits, and herbs of spring and summer.

Cooking outdoors over live fire defines what cooking is for me. It’s simple, it’s tactile, it’s foolproof, and most of all, it brings out the best flavors. No two fires are ever the same, which means your food will never turn out the same way—and that’s a good thing. It’s not about precise cooking times and temperatures but simply paying attention. You don’t have to obsess over perfection, which makes it relaxing and inspiring in ways that other methods of cooking aren’t.

This book translates how I cook at Hartwood to American backyards. Hartwood isn’t a Mexican restaurant; it has always been a marriage of my American training with Mexican ingredients. There are so many ingredients native to Mexico—corn, tomatoes, squash, beans—that define American cooking as well (much of the United States used to be Mexico, after all). Even things like fresh and dried chiles, pumpkin seeds, and tomatillos are becoming part of the American larder and can be found in any large supermarket. So I hope this book represents a modern vision of American outdoor cooking.

The grill described and photographed throughout this book is the exact one I use at home, which is a smaller replica of what I use at Hartwood. It has all but replaced our indoor kitchen. It’s not just for grilling meat: anything cooked on a stovetop—and in some cases, an oven—can be done in my outdoor kitchen. Hopefully, this book will broaden what outdoor cooking means to you. Rather than obsessing over the technical aspects of grilling, I just want you to cook outside and see what happens.

Copyright © 2020 by Eric Werner with Nils Bernstein. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.