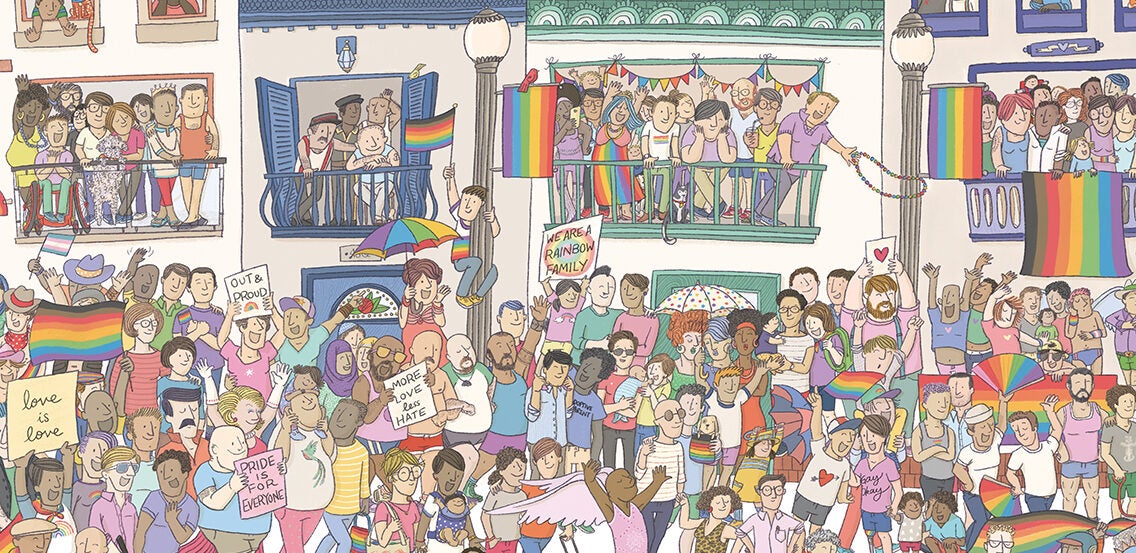

Seeing Queer HistoryThere’s a sign hanging in the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives in Philadelphia—YOU ARE GAY HISTORY—that lets those who enter the space know they’ve come home. Queer archives—the Wilcox, the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, the Botts Collection of LGBT History in Houston, the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC in L.A., San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, Gerber/Hart Library and Archives in Chicago, and New York City’s LGBT Community Center National History Archive, among others—are some of the few distinctly and specifically queer spaces left in the world. In these places, you’re surrounded by miles of materials—books, banners, periodicals, papers, photographs, and ephemera—all of which point to a truth that members of the dominant culture take for granted: you’ve always been here, you always will be here, and you are everywhere.

In his seminal book

Gay New York, Professor George Chauncey tells of when the Dean of the Harlem Renaissance, Dr. Alain LeRoy Locke, sent poet Countee Cullen a copy of Edward Carpenter’s

Ioläus, a 1917 anthology outlining the cultural tradition of romantic male friendship and love. Cullen reported back that he’d read the book in one sitting; the history, he said, made that which people called unnatural seem natural, even beautiful. “I loved myself in it,” Cullen wrote. Today, in cities around the world, archivists and volunteers maintain spaces in which queer people can love themselves and all those who made their lives possible. These places need you, and you need these places.

On Veterans Day 2015, we—Matthew and Leighton—knew almost nothing about queer history, so it’s tough to explain why we ended up at the unveiling of Frank Kameny’s headstone. As a gay couple in D.C., we knew of Kameny, and, while the rest of the city paused to honor those who’d served in the military, we thought it fitting to pay tribute specifically to a queer vet. Gathered at Congressional Cemetery, the small crowd listened as speakers remembered Kameny, the curmudgeonly, brilliant gay rights leader, and we were introduced to a history of which we’d barely heard, details we’d never considered, and people whose names we didn’t know, although they’d dedicated their lives to queer liberation. By the end, we felt overwhelmed, isolated, and angry; we didn’t know

our history.

That’s how it started.

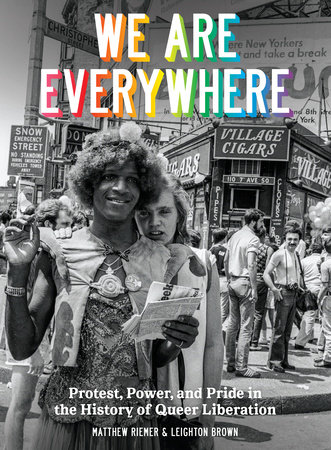

Matthew killed time reading old queer periodicals he found online, while Leighton scoured the Internet for queer photographers and photographs. Looking at the pictures together, we’d get lost for hours; we had a visceral, emotional reaction, as if we’d discovered a family album full of people to whom we were deeply connected—infinitely indebted—and about whom we knew next to nothing. While everyone says a picture is worth a thousand words, that assumes, as William Saroyan wrote, you can “look at the picture and say or think the thousand words.” In the beginning, we didn’t know what the images said; we didn’t have the words. We didn’t know that the queen with the stone-cold stare was Lee Brewster, who helped create Gay Liberation in New York City only to be forgotten; we didn’t know that the badass butch in L.A. was Jeanne Córdova, who seemed always to be on the right side of history; and we didn’t know that the militant AIDS activist from Chicago was Ortez Alderson, whose militance was legendary long before AIDS. Only with time and research did the words and images align.

What began as a hobby became an obsession: we had to figure out as many details about as many photographs as we could; that, in turn, led to atlgbt_history, the Instagram account we started in hopes of sharing what we were learning. We thought we might engage a few hundred people; within a few months, there were ten thousand followers; in just over a year, we’d hit one hundred thousand. As the account grew, we heard from the photographers responsible for, and the people appearing in, the images we posted, those who’d been at the events or who knew the names of the faces featured. We were corrected on details, challenged on choices of language and perspective, and pushed toward grassroots histories that delve into the deep divisions populating the queer past. We faced criticism from people who

knew we’d missed something and demanded we do better. And we got emails, usually from isolated young people, telling us that the accessible introduction to history made them feel less alone.

With few exceptions, those following the account seemed willing to grapple with history, illustrating what James Baldwin said of Black America in 1962: “We are capable of bearing a great burden, once we discover that the burden is reality and arrive where reality is.” The burdensome reality is that queer people in the United States have what Baldwin called “an invented past,” a

story but not a

history. Our truth is not the popular tale of steady progress interrupted by momentary lapses of backlash, but rather a history of constant struggle interrupted by moments of triumph. Because the “Love Always Wins” narrative—the story of a people whose liberation is inevitable, thanks to a generally just society—is easier to market, however, we’re constantly battling a type of “historical amnesia,” as Audre Lorde wrote, that “keeps us working to invent the wheel every time we have to go to the store for bread.”

A fundamental part of the oppression queer people experience at the hands of the dominant culture is a denial of our history, an erasure of our unique existence in decades and centuries past. Although the majority is ultimately responsible for this oppression, “we must be responsible for our liberation,” and we therefore have an obligation not only to each other but also to those who came before and those yet to arrive. “Each one of us is here because somebody before us did something to make it possible,” Lorde taught. If more queer people had access to their history, and if those who

had access took advantage of it, perhaps, as activist/photographer Morgan Gwenwald observed, “they would be more sensitive to the possibility that their event/idea/product might not be a ‘first’ and that some acknowledgment to those who have come before should be made.”

“We choose the history that we say is ours and by so doing,” wrote Lesbian Herstory Archives cofounder Joan Nestle, “we write the character of our people in time.” Our queer invented past—the character of

our people—too often consists of stories of strikingly American gays who wanted to be “like everybody else,” presented by strikingly American gays who want to be “like everybody else.” Names, places, events, and issues are picked from the infinite past as those most likely to further the finite aims of the present: we’ve

always been in your military, let us serve openly; we’ve

always had families, give us your blessing; we’ve

always run your companies and your towns, let us do so free from sanctioned discrimination. Although this approach isn’t in and of itself problematic, we mustn’t “use history to stifle the new or institutionalize the old.” Queer military members, queer parents, queer politicians, and queer businesspeople deserve the respect they’ve earned—which, in many cases, is infinite—but so do queer pacifists, queer sex workers, queer artists, and queer communists. Today, one need look no further than the White House or the local police station to know that the institutions into which lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people continue to seek acceptance harbor deep reservoirs of hate, chauvinism, homophobia, and paranoia. Why, then, are we trying to be “like everybody else”? You can “never be

like them,” Sylvia Rivera said, and, by longing for normality, “you are forgetting your own individual identity.” The very source of queer power, Nestle wrote, is that our “roots lie in the history of a people who were called freaks.”

We—the authors—didn’t understand or embrace this power until we started to

see queer history through photographs that provide, as Susan Sontag wrote, “the principal access to realities of which we have no direct experience.” Photographs, Gay Liberation–era photographer Steven Dansky notes, “make visible what is concealed and become evidence of reality—a photograph is a powerful record of the social space.” For queer people being the subject of a photograph will always be “daring and risky,” a “physical declaration of political and sexual identity” that may or may not fit into simple definitions and dominant narratives. “Our visibility is a sign of revolt,” bisexual activist Lani Ka’ahumanu said in 1993. “We cannot be stopped. We are everywhere.”

Copyright © 2019 by Matthew Riemer and Leighton Brown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.