Introduction

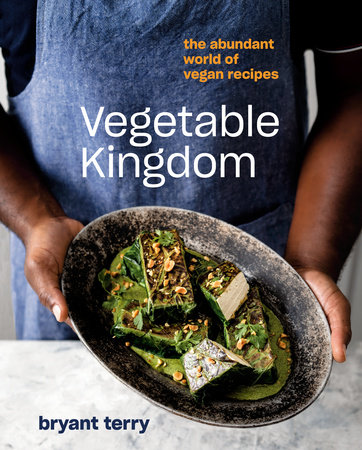

Fennel for Zenzi

Vegetable Kingdom is inspired by my daughters, Mila and Zenzi. They have blessed this book like my ancestors blessed meals, by humbling me to that which is greater than myself. When Mila pulls a gloriously resonant hum out of her cello and when Zenzi dances in energetic spins and wild flourishes, they are turning the love and effort I pour into them into a vitality and power that they will carry far beyond what I could ever know. I wrote this book to make a diversity of foods of the plant kingdom irresistible to them, to inspire their curiosity, and to show them the pleasure of a lifelong adventure with good, nourishing food. That mission drives this book.

Vegetable Kingdom reflects the essence of how my wife, Jidan, and I root and raise our children. Mila and Zenzi have been rooted in the garden with farm-fresh ingredients and raised on a diversity of dishes, springing from the deep well of Black and Asian foodways. We help shape their multicultural identity organically by creating and consuming Afro-Asian food and the spectrum of flavors they engage, often in the same meal. While I emphasize ingredients, cooking techniques, and classic dishes of the African Diaspora, Jidan does the same with Asian food—Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese. So this book features a number of ingredients and flavors from East and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and the American South. With such an expanse of cultural ground to cover, it is serendipitous that it was the Mediterranean—a region at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, and Europe—and one of its hardiest vegetables, fennel, that acted as a catalyst for unifying the dynamic spirit and energy that permeates this book.

A few years ago, I was at the farmers’ market checking out the late summer/early fall bounty: flavorful Seascape strawberries, fresh cranberry shelling beans, vibrant Red Burgundy okra, and plump pomegranates, to name a few. That morning, fennel was all over the place. The bulbs glowed bright white. The stalks and fronds were moist and fresh, and their aniselike aroma was strong. One stand offered samples of crunchy sweet slices with fresh lemon juice squeezed over them. I had never really bought fennel unless a recipe required it, but that day the fennel was calling me! Ya boy bought four bunches on the strength of that smorgasbord for the senses. Driving home, I decided I would use every part of the fennel. I envisioned the feathery fronds as a garnish, flashing back to Instagram posts by some of my favorite chefs (like JJ Johnson, Rob McDaniel, and Jeremy Fox), creatively balancing color and making dishes pop by arranging fresh herbs, microgreens, and citrus zest on top of them. I figured I would put the fennel stems into the freezer, along with other vegetable scraps reserved for stocks. I had no idea how I would cook the bulb that day, even though it’s the only part I really used in the past.

Regardless of how I prepared the fennel, I was a little nervous that Zenzi, my five-year-old, would not be into it. Mila, my eight-year-old, has always had an adventurous palate; she loves to try different cuisines and takes pride in eating unfamiliar dishes. Zenzi, on the other hand, would be happy if she had pasta, bread, and crackers at every meal.

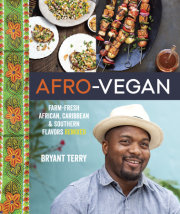

My other goal was to create a dish through the lens of the African Diaspora. Inspired by visual artists Romare Bearden, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Deborah Roberts, and Derrick Adams, as well as some of my favorite hip hop producers like Prince Paul, The Bomb Squad, DJ Premier, RZA, Organized Noise, and Madlib, I have approached recipe development as a collagist—curating, cutting, pasting, and remixing staple ingredients, cooking techniques, and traditional Black dishes popular throughout the world to make my own signature recipes. But this approach is bigger than creating cookbooks.

Many people build altars, visit gravesites, and reminisce with photos to engage with loved ones who have passed. For me, recipe creation is a praxis where I honor and bring to life the teachings, traditional knowledge, and hospitality of my blood and spiritual ancestors by making food. While it may not be obvious, most recipes that I develop stand on the shoulders of relatives, mentors, historical heroes and heroines, and those who inhabited the land on which I live and work. Educating my girls about and introducing them to foods and flavors of the African Diaspora allows me to teach history and share memories with them; it helps them learn about and take pride in the contributions of their ancestors, culinary and otherwise; and it celebrates foods of the African Diaspora in a world where European cuisine is at the center and Black food is often at the margins.

So how did I Blackify fennel, use the entire vegetable,

and create a recipe that even the most finicky eaters would enjoy? In my first pass, I pan-seared it in olive oil, then basted it in a tangy citrus and garlic-herb sauce inspired by mojo, a condiment/marinade popular in Cuban cooking. It was solid, but something was missing. To bring more complexity and balance while building on the Afro-Caribbean theme, I thinly sliced some of the fennel stalks and added them to the sauce while simmering and basting the fennel. I also pulverized savory plantain chips in a spice grinder and sprinkled the powder on top before serving. The fennel was fire! It even passed muster with my girls: As I nervously looked on during dinner, they were all smiles, and they couldn’t get enough of the plantain powder. Turned out, freestyling an African Diaspora–inspired vegetable dish (that kids enjoyed) was easier than I thought.

Our girls tasted and approved most of the recipes in this book, so even if dishes don’t appear to be “kid-friendly,” they are. In fact, I want real food to be seen as kid-friendly. It incenses me when we eat at nice restaurants and the kids’ menu is limited to hot dogs, fries, and chicken fingers, when it could flourish with Millet, Red Lentil, and Potato Cakes (page 175), Pan-Seared Summer Squash Sandwiches (page 121), and Jerk Tofu Wrapped in Collard Leaves (page 143). We serve our girls whole-food meals at home, but the idea that kids can’t enjoy what adults eat is horribly reinforced when those menus bearing heavily processed crap and edible food-like substances are plopped in front of them as soon as they sit down. At home I will often take the most obscure vegetables and prepare them in familiar ways so that Mila and Zenzi raise their food IQ and expand their palates. Throughout writing

Vegetable Kingdom, I realized that this educational approach would apply to anyone. You may not have tried (or heard of) kohlrabi, but I promise you’ll be hooked once you simply coal-roast it and serve it with a west African–inspired peanut sauce, garnished with peanuts, Fresno chiles, and lemon zest.

Even the structure of

Vegetable Kingdom was inspired by my daughters. I initially planned to organize the book around the four seasons, as I mostly build meals with an eye on the beautiful, seasonal produce growing in our home garden or piled on tables in farmers’ markets throughout Northern California. But after Mila mentioned that her gardening class at school classifies vegetables according to which part of the plant is eaten, I decided to follow that structure for this book: Seeds, Bulbs, Stems, Flowers, Fruits, Leaves, Fungi, Tubers, and Roots. For vegetables that fall into multiple categories, I strive to use all parts of the plant. For example, beets offer their commonly used roots, as well as their delicious, edible leaves, which are too often discarded.

The literal vegetable kingdom is vast; this is just my snapshot. In

Vegetable Kingdom, you’ll find more than 175 recipes (including subrecipes and pantry items) that bring out the best in more than thirty vegetables. I also share my favorite tools, tips, and ideas for cooking vegetables and building creative meals on your own. You can find most ingredients at a farmers’ market or quality supermarket, but you might need to visit specialty grocery stores or order some ingredients online. It’s worth it to get the full flavor of the recipe and to fall in love with vegetables, grains, or legumes you’ve never had before. My sincere hope is that this book effects real change in your world by inspiring your journey into the vast and verdant pleasures of botanical bounty. If this book moves you to try new vegetables, and to think more critically and creatively about how and what you eat, I’ll have fulfilled the calling to create this homage to health as learning and pleasure. Now, go forth, and explore

Vegetable Kingdom.

Copyright © 2020 by Bryant Terry. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.