When I wrote my first cookbook, Into the Vietnamese Kitchen, interest in the food of Vietnam was nascent and mainly occupied foodies and culinary geeks like me. Many of the ingredients called for were available at supermarkets, but to present the richness of Vietnamese cuisine I had to ask cooks to shop at Asian markets for a specific quality of fish sauce and noodles. I was trying to stay as true as possible to the flavors and textures of traditional dishes, all the while reflecting my experiences as a Vietnamese American. A lot has changed since that book released in 2006. An uptick in media coverage of Vietnamese food in print, television, and online made it trendy. Tourism and business in Vietnam increased—former president Barack Obama met up with Anthony Bourdain in Hanoi to sample bún chả(grilled pork with rice noodles and herbs, see page 201). Sriracha, a Thaihot sauce that had become a mainstay at Viet restaurants, has practically become an American staple. Even tofu has gained wider acceptance. My cookbooks on banh mi and pho, released, respectively, in 2014 and 2017,spotlighted Vietnam’s signature dishes in traditional and modern incarnations. (Mexican bolillo rolls are fabulous for Viet sandwiches! Pressure cookers make pho doable for weeknight eating!) Writing those books for a broader audience meant spending more time where most Americans shop for food—the supermarket. And being a busy writer, I also learned how to fit good, interesting food into hectic lifestyles.

In my hometown of Santa Cruz, California, as well as cities I’ve visited, I noticed a steady change in the Asian food sections of local supermarkets; there was a much greater variety, which went beyond the usual suspects of Chinese and Japanese soy products. More important, I could purchase seeds of my supermarket obsession brands that I used to find only at Asian markets, such as Chaokoh coconut milk; Sun brand’s Madras-style curry powder, a family favorite, could be found in the regular spice aisle; and quality white and quick-cooking brown jasmine rice were in the Asian aisle and regular rice section.

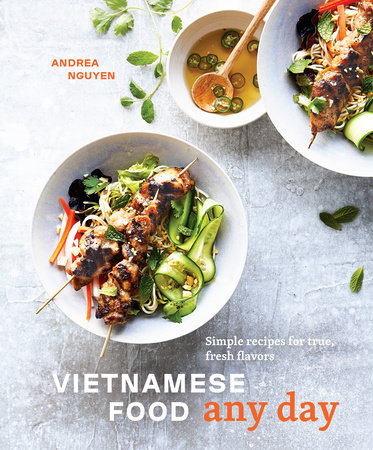

The diversification of American supermarkets has been tremendous. According to the Food Marketing Institute (a trade group), in 1975, supermarkets carried about 9,000 products. Today, the average supermarket has roughly 40,000 items. Too many choices can confound (which is why cellphones are common grocery-shopping lifelines), but I see them as an opportunity to help cooks shop wisely and mine the resources at their fingertips to make good Vietnamese food. For example, trends in gluten-free and whole foods nudged pasta companies to develop white and brown rice capellini and spaghetti—terrific subs for traditional Vietnamese bún (round rice noodles).I use rice spaghetti for Spicy Hue Noodle Soup (bún bò Huế, page 89), and the capellini is great for rice paper rolls (see page 119), lettuce wraps (seepage 139), and rice noodle salad bowls (see page 197). Pomegranate molasses (see page 34) and juice are my tart-sweet stand-in for tamarind, which has yet to be widely distributed. Fresh turmeric, coconut water, and coconut oil may be new health-boosting ingredients to some people, but to me, they’re game changers for creating vibrant flavors that beautifully capture what I’ve enjoyed in Vietnam. Realizing that a wider array of Viet dishes can be part of the American table, I decided to write Vietnamese Food Any Day based on ingredients found at most mainstream market chains such as Kroger, Whole Foods, Albertsons, Trader Joe’s, Publix, and Giant Eagle. I’ve also canvassed Costco and Walmart. And whenever possible, I’ve scoped out well-stocked independent markets too. Given the reasonable inventory overlap between mainstream and ethnic grocers, there’s no Asian-market shopping required for this book. That said, this book’s approach to showcasing Vietnamese cuisine isn’t hodgepodge. It’s based on a Vietnamese term, khéo, that means“smart” and “adroit,” but when applied to cooking, it conveys food that’s been thoughtfully and skillfully prepared with intention and a grounding in the fundamentals.

In the spirit of khéo cooking, the recipes herein are streamlined but not dumbed down. They capture the essence of Vietnamese foodways, while demystifying and decoding the cuisine for home cooks. Simple recipes that I’ve gathered from Vietnam, such as the Grilled Slashed Chickenon page 98, underscore the cuisine’s possibilities. On the other hand, reimagined classics prepared with nontraditional ingredients, such as the Smoked Turkey Pho on page 84, will inspire you to improvise. Developed to be fun and/or low-stress, the recipes are prepared with regular pots and pans (no wok or Chinese steamer is required), a pressure cooker, anda microwave oven. There’s no deep-frying, because as much as many of us love eating fried food, few of us want to make it and clean up afterward.

We’re cooking and eating in very exciting times. The tumultuous history of Vietnam, informed by its regional differences, varied topography, and extensive interactions with foreign peoples through colonial occupation, war, and diaspora, laid the foundation for a lot of make-do cooking. Viet cooks are curious and inventive by nature. They’re always creating new dishes, incorporating new ingredients, or reconsidering old-fashioned, labor-intensive techniques. That dynamic keeps the cuisine and culture evolving. This cookbook will help you plug into that mindset to make Vietnamese food. Through preparing recipes in

Vietnamese Food Any Day, you’ll come to understand how Vietnamese flavors may be built, how to put together a Vietnamese meal,and how to incorporate Vietnamese cooking into your repertoire. Viet food doesn’t have to be an exotic, special weekend project. It’s deliciously doable whenever you want.

Copyright © 2019 by Andrea Nguyen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.