1

“What’s so great about going to the grand opening of the park tomorrow?” I ask my sister Alfie, as I make a snow angel on her fluffy bedroom rug. “So they fixed it up a little. It will still be the same old boring place.”

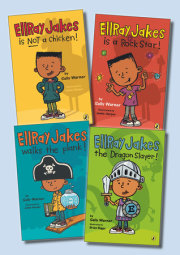

My name is EllRay Jakes, and I am eight years old. I know this kind of stuff.

“Nuh-uh,” four-year-old Alfie argues, scowling. “It said ‘new’ on the sign in the post office, didn’t it? And signs don’t lie. It’s against the law. There’s gonna be fwee hot dogs, Mom said, so we each get to ask a fwend.”

“Fwee” means “free” in Alfie-speak. And “fwend” means “friend.” Alfie’s r’s sort of come and go.

I sigh. “A park’s not new just because they plant better grass, and change the benches so people can’t sleep on them, and paint over the graffiti. Dad said that’s all they were going to do. And it’s January, Alfie. It might be raining.”

“But there’s probably a better play area now,” Alfie says, ignoring my weather forecast.

The old play area at Eustace B. Pennypacker Memorial Park only had one swing set, and one tetherball pole that has been missing its actual ball for almost a year, I remind myself. So it would be hard to make the play area any worse.

“Listen, Alfie,” I say. “We already saw the so-called new park the other day, didn’t we? When Mom got lost on the way to Trader Joe’s? We drove right by it.”

Our mom sometimes goes a different way to the store when traffic gets too crowded. She also likes to park our Toyota with plenty of space on each side, even though the car is older than I am.

Mom is a very careful driver.

I am going to have the coolest car ever, when I grow up! It will always be new, and it will have flames painted on the sides. Or at least skinny stripes.

“But when we saw the park, it didn’t have a wibbon in fwont of it for our queen to cut with giant scissors, EllWay,” Alfie says, as if I have just missed the most obvious point about Oak Glen’s newest old park, which is opening tomorrow morning, like I said. Saturday.

“EllWay” is Alfie’s version of “EllRay,” which is a shorter—and less awful—version of “Lancelot Raymond,” my full, official name.

My mom writes love stories for ladies, see, about dead or imaginary kings and queens. I guess she got a little carried away naming me when I was born. Moms sometimes do that, in my opinion. And my college professor dad was probably too busy studying weird rocks to put up an argument.

Later, as time went by, my too-fancy name was shortened first to L. Raymond, and then to L. Ray.

But now, everyone just calls me EllRay.

And I won’t do much more translating for Alfie, I promise.

“This is California, Alfie,” I remind her. “Oak Glen doesn’t have a queen. That lady you’re talking about is our new mayor. She just acts like a queen.”

The new mayor shows up everywhere, wearing a fancy hat. It is the only ladies’ hat in Oak Glen, I think. She also waves a lot.

I try not to sigh again as I click my robotic insect action figure—already cool enough!—into a deadly-looking tank. I start rolling it toward the lavender pony whose long blond tail Alfie is combing. I imagine destroying its golden corral.

C-r-r-r-u-n-c-h!

Nothing personal, lavender pony.

“That lady is too the queen,” Alfie informs me. “Just because she doesn’t wear her queen-hat all the time,” she adds, shaking her own head so hard that her three soft, puffy braids swing back and forth. “You probably think she should wear it to bed, don’t you?” she continues. “Or when she goes swimming? But real queens don’t do that. I asked Mom once, and she said no. So, hah.”

Alfie has recently discovered sarcasm, I am sorry to say.

“You’re mixing stuff up,” I tell her. “First, it’s called a crown, not a ‘queen-hat,’” I begin. “And second—”

But Alfie has moved on. “You don’t have anyone to invite to the park,” she interrupts. “Because you’re running out of fwends.”

I feel my cheeks get hot, because what Alfie just said is basically the terrible truth. And I’m her big brother, and she needs to look up to me! “What? I am not running out of friends,” I argue, but I don’t sound very convincing.

“Well, I have Suzette, Arletty, and Mona to choose from,” Alfie says, setting aside her star-spangled horse to argue with me. “And you just have Corey, only he’s always busy swimming.”

My best friend, Corey Robinson, is an eight-year-old swimming champion. He will probably be in the Olympics some day, everyone says.

I don’t know what his plans are after that. Neither does he. His parents haven’t told him yet.

“I have other friends, too,” I tell Alfie. “What about Kevin?”

Kevin McKinley is the only other boy with brown skin in Ms. Sanchez’s third grade class at Oak Glen Primary School, in Oak Glen, California. He has been one of my two best friends for a couple of years. But lately, he’s been hanging out a lot with a couple of kids who live on his street, but who go to private school. I don’t even know their names.

It’s too risky for me to ask Kevin to come to the park tomorrow, even though he really, really likes hot dogs. He might say no! Or he could tell the other guys in our class that it’s babyish for an eight-year-old to care about a new play area in some lame new-old park.

And then our friendship would really be over.

“I thought you said Kevin was sometimes Jared’s fwend now,” Alfie says.

Jared Matthews, my part-time enemy.

“I never told you that,” I object. “Anyway, it changes around. And since when do you keep track of my life? Mind your own business, Alfie. You’ve got enough problems.”

“You need a spare fwend,” Alfie tells me, ignoring what I just said about problems. “You know,” she says, grabbing another horse to brush. “The way Mom’s car has a spare tire.”

Both of us were in my mom’s car last week when it got a flat tire on San Vicente Street, which is always super busy. Mom steered our wobbling car over to the side of the road. She told us to stay put while she called for help. But it was scary, waiting in the backseat as all that traffic whizzed by. I pretended it wasn’t scary, though, because of Alfie.

I look out for her—in secret.

The spare tire that the auto club guy put on our car looked like it belonged to a clown car, it was so little. I was embarrassed for our poor Toyota.

I don’t want a spare friend like that!

I’m already the smallest kid in my class, aren’t I? I could use someone big.

“You know,” Alfie continues. “A spare. For emergencies, like this one.”

“For your information, Alfie, going to Pennypacker Park for a free hot dog isn’t an emergency,” I tell her, getting to my feet.

Alfie and her goofy opinions can just stay here playing with sparkly fake horses, I tell myself. I am trying to ignore the voice in my head that is saying she’s a little bit right.

“You should hold an audition,” Alfie announces before I can escape. “That’s what we’re doing at my school. It was all Miss Nancy’s idea.”

Alfie goes to Kreative Learning and Daycare, even though they spell “creative” wrong, which drives my dad bonkers. “You’re auditioning friends at daycare?” I ask, tossing in a little sarcasm of my own.

“No,” Alfie says, calm as anything. “We auditioned for our spring show last week. The best part of the show is called Brown Bear, Brown Bear. And I’m gonna be the star. Mom already started making my costume.”

“You’re the bear?” I ask, my forehead wrinkling. Because usually, Alfie is more of a kitty or a bunny or a sparkling pony kind of girl.

She might make an exception if she could be a panda, but Ms. Sanchez says pandas aren’t really bears. Anyway, they’re black and white, not brown.

“I’m the goldfish,” she says, sighing at having to explain something so simple. “I want to be the last animal everybody sees, so I’ll get all the clapping. I figured it out.”

“Good luck with that,” I call over my shoulder as I leave Alfie’s pink and purple palace. I mean room.

“At least I have fwends!” Alfie yells after me.

2

Okay, so I went to the grand re-opening of Eustace B. Pennypacker Memorial Park yesterday without bringing anyone with me. So what?

But it made me think about what Alfie said.

Maybe I am running out of fwends. I mean friends.

Everyone in my class seems to like me just fine, except for Jared Matthews, sometimes. But he takes turns being grouchy with everyone. And Stanley Washington is kind of like Jared’s personal assistant, the way Fiona McNulty is Cynthia Harbison’s personal assistant, so sometimes he stays away from me, too.

Cynthia says that movie stars have personal assistants, so why not her?

It’s her latest thing.

Cynthia is basically the girl version of Jared in our class, only worse. She thinks faster than Jared, and she speaks up quicker.

I will take a new look at all the guys in my class before school starts tomorrow morning. It would be great to make at least one spare friend by this Friday, because that’s when Alfie’s show is going to be. My new friend and I can sit through that, then we will all go out for pizza or ice cream, so that will be fun. And then we can have a sleepover, which will be the most fun of all.

I already know Corey can’t do it, because he has swim practice every Saturday morning. Early, like at six-thirty.

There are only ten boys in Ms. Sanchez’s third grade class, and there are fifteen girls That means the girls are winning—in population, anyway. But it also means there are five other guys in my class—besides Corey, Kevin, Stanley, and Jared—for me to be friends with. Maybe.

The five extra boys are: Major Donaldson, Marco Adair, Nate Marshall, Jason Leffer, and Diego Romero.

Those are my possibilities.

Major mostly hangs out with Marco. In fact, Ms. Sanchez sometimes calls them “M and M” for short. When she calls on Marco in class, though, she usually calls him Mr. Adair, because when she accidentally calls out, “Marco,” someone always says, “Polo!”

And everybody laughs.

Third-graders need easy stuff like that to laugh about, in my opinion. Our school days are long, and we get desperate for entertainment.

There are lots of reasons to like Marco Adair. He’s always fair with the kickballs, and with choosing sides when we play games at recess. Also, he can make funny armpit noises better than any other boy in our class. Only on the playground, of course. Ms. Sanchez is not the type of lady who would think it’s funny when you make your armpit go flirrrrppt.

Major Donaldson is cool, too. In fact, my dad claims that Major has the best name in the world, because the word “major” means so many different things.

1. Major can mean important, like when someone says, “This is really major.”

2. It also has something to do with music. I forget what.

3. And in college, Dad says that your major is the main thing you study. For example, my dad’s major was geology. My mom’s major was comparative literature, whatever that means. I don’t know yet what my major in college will be. Maybe the History of Video Games?

4. But best of all, a major is a very important officer in the armed services, like the army or the marines.

My dad teases, threatening to salute whenever he sees Major Donaldson. That’s the kind of sense of humor he has.

The only problem is, Marco and Major are so tight that it might be hard to squeeze my way into being their friend. There might not be enough room. They’ve known each other since kindergarten, and they’re not sick of each other yet.

Nate Marshall is another friend possibility, though. He doesn’t hang with anyone special. His red hair sticks up in front, like he’s got a little rooster crest there. But on him it looks good—like an exclamation point.

. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.